William Duke of Normandy’s historic victory over the Saxon army of King Harold on 14th October 1066

Last Stand of King Harold at the Battle of Hastings on 14th October 1066 in the Norman Invasion: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

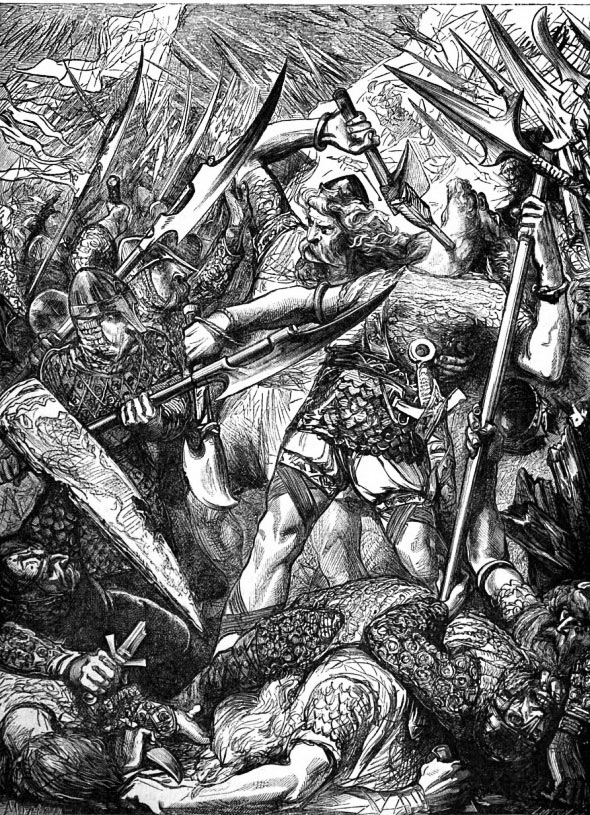

Death of King Harold at the Battle of Hastings on 14th October 1066 in the Norman Invasion: picture by James Cooper

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Stamford Bridge

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of the Standard

To the Norman Invasion of Britain index

Battle: Hastings

War: The Norman Conquest of England

Date of the Battle of Hastings: 14th October 1066

Place of the Battle of Hastings: On the Sussex coast of England

Combatants at the Battle of Hastings: The Norman, Breton, Burgundian, Flemish and French army of Duke William of Normandy against the Saxon army of King Harold of England

Generals at the Battle of Hastings: Duke William of Normandy against King Harold Godwinsson of England

Size of the armies at the Battle of Hastings: The armies probably numbered around 5,000 to 7,000 on each side, although some traditional accounts give the numbers as much higher.

Costume, arms and equipment at the Battle of Hastings: The Battle of Hastings saw the clash of two military systems. The Saxon army, centred on the King’s personal bodyguard of “housecarles”, comprised the universal levy, the “Fyrd”, led by the local leaders of each shire with their households

The Fyrd, containing large numbers of ineffective peasants along with the warriors of each shire, fought in wedged shapes battalions, the point of the wedge formed by the best equipped soldiers, the remaining men, armed with spears and whatever weapons they had, forming the rear ranks. The favoured weapon of the professional warriors was the battle axe. The Saxon army fought on foot, nobles and men-at-arms dismounting for battle.

The Normans and the other Frankish contingents in William’s army fought in the manner developing across mainland Europe, a mix of archers, dismounted soldiers and above all mounted knights.

The soldiers on either side who could afford it wore leather jackets with steel chain or ring mail sewn into the leather and a conical helmet with a nose guard, carrying a spear, sword and the characteristic kite shaped shield. Archers in the Norman army were armed with a short bow.

The significant features of the battle were the manoeuvrability of the Norman mounted knights, the terrible power of the Saxon battle axe and the impact of the Norman arrow barrage.

Winner of the Battle of Hastings: The Normans, overwhelmingly.

Account of the Battle of Hastings: William, Duke of Normandy, launched his bloody and decisive invasion of Saxon England in 1066. In that year Edward the Confessor, King of England, died without heir, appointing by his will Harold Godwinsson, son of England’s most powerful nobleman, the Earl of Wessex, as his successor. Across the Channel, William of Normandy considered himself rightfully the next King of England, basing his claim on a promise by Edward the Confessor in the early 1050s and an oath of fealty sworn by Harold during an enforced visit to William’s capital at Rouen following his capture by the Count of Ponthieu.

Succeeding to the dukedom of Normandy as a bastard child of Duke Robert, William devoted his early adult life to enforcing his authority in a succession of ruthless campaigns, meanwhile building his dukedom into a fearsome mini-state, efficient both administratively and militarily.

In the summer of 1066 William assembled an army of noblemen and adventurers from across Northern France to invade England, promising lands and titles in his new kingdom to his followers and obtaining the support of the Pope for the venture.

A fleet of around 1,000 vessels, designed in the style of the old Norse “Dragon Ships” (80 feet long; propelled by oars and a single sail), was built and assembled to convey the army across the Channel.

Duke William stumbles on landing in England: Battle of Hastings on 14th October 1066: picture by Cecil Doughty

Among the fighting knights of Northern France who joined William were Eustace, Count of Boulogne, Roger de Beaumont and Roger de Montgomerie. The clergy was well represented; among them Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, William’s half brother, and a monk René who brought twenty fighting men and a ship, in the expectation of a bishopric in England. Robert le Blount commanded the fleet.

It was no secret that William intended to invade England. He had sent an insulting demand that Harold pay him homage and the gathering of the troops and ships had northern France in turmoil, causing Harold to assemble a powerful army along the Sussex coast in defence.

William’s fleet lay ready to cross the Channel, after being held in port for the duration of the summer by contrary winds, when Harold received the news that a Norwegian army led by King Harald Hadrada with Harold’s renegade brother Tostig had landed in Yorkshire after sailing up the Ouse.

Harold marched his army north and routed the invaders at the battle of Stamford Bridge, in which both Harald Hadrada and Tostig were killed.

The timing could not have been worse for the Saxons. The winds changed and William’s fleet crossed the Channel, landing on the Saxon coast unopposed on 28th September 1066.

Harold received the news of the Norman landing in York soon after his triumph over the Norse invaders and determined to march south immediately to do battle with William.

The Minstrel Taillefer leads the Norman attack juggling his sword and singing the ‘Song of Roland’: Battle of Hastings on 14th October 1066 during the Norman Invasion: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

Harald Hadrada’s army had been nearly annihilated in the savage fighting at Stamford Bridge but the Saxons had suffered significant losses. The King’s brother, Earl Gurth, urged a delay while further forces were assembled but Harold was determined to show his country that their new king could be relied upon to defend the realm decisively against every invader.

Battle of Hastings; the deaths of King Harold’s brothers,

the Earls Gurth and Leofwin: a scene from the Bayeux Tapestry

Safely landed at Pevensey Bay, William built a fortification and then moved further east to Hastings; his troops ravaging the countryside which was known to be part of Harold’s personal earldom.

The Saxon army arrived in the area on 13th October 1066 and established a position on a hill north west of Hastings, known subsequently as Senlac (sang lac or lake of blood); putting up a rough fence of sharpened stakes along his line, fronted by a ditch. Harold issued orders as compelling as he could make them that, when throughout the battle, his army was not to move from this position, whatever the provocation.

Early on 14th October 1066 William moved forward with his army to attack the Saxon position, the Normans in the centre flanked on the left by the Bretons and on the right by the rest of the French.

The battle was fought over the rest of the day, a savage fight with heavy casualties on each side. The issue in the balance until late in the afternoon; marked by repeated cavalry attacks on the Saxon position by William’s cavalry, violently repelled until the final assaults. The Normans found the Saxon warriors with their battle axes, and in particular Harold’s “housecarles”, a formidable enemy. There were many accounts of knights with their horses being hacked in pieces by these terrible weapons wielded in great swinging blows.

Battle of Hastings on 14th October 1066: King Harold is shown plucking the arrow from his eye: a scene from the Bayeux Tapestry

At around midday an assault developed on the Saxon camp causing a section of Harold’s line to retreat in confusion. Reaching the top of an incline the Saxons turned on the pursuing Normans, held up by a ditch across their front, and drove them back with considerable loss.

In the early afternoon William’s left flank of Bretons gave way, to be pursued down the hill by the fyrd they had been attacking. This break in the line, that Harold had so adamantly warned against, gave the Normans the opportunity to break into the Saxon position at the top of the slope. The incessant Norman attacks began to break up Harold’s army; the barrage of arrows taking a heavy toll, in particular wounding Harold in the eye.

During the course of the battle William had three horses killed under him and was forced to ride round the field, his head bared, to reassure his army that he was unhurt; assisted by his half-brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, in rallying the Norman soldiers.

A particularly savage fight developed around the position held by the now severely wounded Harold and his royal housecarles. Finally the Saxon King was killed, followed by his brothers, Earl Gurth and Earl Leofwin, and the remaining housecarles.

It was late afternoon and much of the remnants of the Saxon army gave way, fleeing the field; although a significant force continued to fight. The battle finally ended with all the remaining Saxons killed.

The heaped bodies were cleared from the centre of the battlefield, William’s tent pitched and a celebratory dinner held.

Casualties at the Battle of Hastings:

The figures are unknown but were heavy for the Normans and disastrous for the Saxons.

Follow-up to the Battle of Hastings: It was some time before Saxon England acknowledged William as king. William was forced to march to the West and cross the Thames at Wallingford in Oxfordshire before circling round from the North and capturing London, devastating the countryside as he marched. The Tower of London was the first of the castles William built to dominate and subjugate England. William was finally crowned in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066 by the Saxon Archbishop, Aldred of York.

In March 1067 William returned to Normandy, leaving Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, to continue the process of building castles and subjugating the population. William only returned to England on four further occasions.

William the Conqueror died following the capture of Mantes in 1087, leaving England to be ruled by William II and Normandy by his eldest son Robert.

Probably only 20,000 Normans and other Frenchmen came to England as a result of the Conquest. Nevertheless the Saxon country was transformed, French becoming the language of administration and government and the Conqueror’s followers displacing the native nobility. The Saxons lamented their lost freedom for two centuries while England now looked across the Channel for cultural and political inspiration.

Conquest in France remained the obsession of the Frankish kings of England until the 16th Century. French names predominated among the nobility and the military classes; doubtless the Montgomery leading the British armies in the Second World War was a descendant of the Roger de Montgomerie who fought for the Conqueror.

Death of King Harold at the Battle of Hastings on 14th October 1066 in the Norman Invasion: picture by James William Edmund Doyle

The Bayeux Tapestry: A remarkable feature of the Norman Conquest was its near-contemporaneous record in the Bayeux Tapestry; strictly a work of embroidery rather than tapestry (being embroidered on cloth rather than woven into it). The origins of the tapestry, lodged in Bayeux Cathedral, are uncertain; perhaps executed at the direction of William’s wife Matilda or by seamstresses in England at the direction of Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, and, after the Conquest, Earl of Kent, and given to the Cathedral at Bayeux by its bishop.

The Tapestry illustrates the various stages of the conquest, providing detail that is not available in the written accounts.

The original Tapestry is displayed in Bayeux and a copy in the City Museum at Reading in Berkshire.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Hastings:

- Duke William’s mother was Arlette, a tanner’s daughter. The garrison of a French town under siege by William hung animal hides over the walls as a taunt on his origins. They regretted the joke when William took the town and put the garrison and population to the sword.

- At his birth William grabbed the straw causing onlookers to comment on his determination. When his father, Duke Robert, left for the Crusades he appointed his little bastard son, William, as his successor.

- As William disembarked in England he stumbled and fell, to the dismay of his soldiers who took this as an ill-omen. William quickly held up handfuls of sand and said “Look I have already taken the land.” Some days later, arming for the Battle of Hastings, William put his hauberk on back to front, again causing adverse comment among his superstitious followers. “Just as I turn the hauberk round, I will turn myself from duke to king”, said William, clearly never at a loss for “le bon mot”.

- The Pope provided William with a battle standard, carried at William’s side during the Battle of Hastings by a knight called Toustain, after two other knights had declined the dangerous honour.

- The Norman army was said to have been led into battle at Hastings by the jongleur, Taillefour, who repeatedly tossed his sword in the air and caught it, while singing the “Song of Roland”.

- Tradition has it that Harold was shot in the eye by an arrow. There seems some uncertainty about this, although the Bayeux Tapestry shows Harold plucking out the arrow. Traditionally, death by transfixing through the eye was the fate of the perjurer, the character William sought to give Harold for failing to comply with his oath of fealty. Harold may simply have been overwhelmed by the Norman soldiery without any such particular arrow injury.

- Numbers of militant clergy fought at the Battle of Hastings in William’s army. In order to comply with the oath of ordination, that priests might not shed human blood, clergymen like Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, and Geoffrey, Bishop of Coutances, armed themselves with bludgeon type implements rather than bladed weapons, using them to beat their adversaries’ brains out.

- After the battle William had Harold’s body thrown into a pit, claiming he had perjured his oath to allow William to take the crown of England. Later the corpse was removed and re-interred at Waltham, Harold’s favourite religious shrine. It is said that Harold’s body was recognised on the battlefield by his queen, Eadith of the Swan’s Neck.

- A rumour persisted that Harold survived the battle and lived as an anchorite in the area, finally confessing his true identity on his death bed.

- A force of exiled Saxons served as the Varangian Guard of the Byzantine Emperor, fighting as before on foot with battle axes. The Varangian Guard was bloodily annihilated fighting the Frankish Crusaders, as their brothers had been at Hastings.

- The best remembered feature of William’s administration in England was the survey of resources known as the Domesday Book prepared in 1085 to 1086.

References for the Battle of Hastings:

- The Bayeux Tapestry by Collingwood Bruce.

- Fortescue’s History of the British Army volume I.

- British Battles by Grant, volume I.

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Stamford Bridge

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of the Standard

To the Norman Invasion of Britain index

Annexe for the Bayeux Tapestry:

Bayeux Tapestry 1: Harold attends the court of King Edward the Confessor before his journey to Normandy

Bayeux Tapestry 2: Harold attends the court of King Edward the Confessor before his journey to Normandy