The account of General Braddock’s expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755:

Part 8: Braddock’s army’s march from Fort Cumberland to Little Meadows

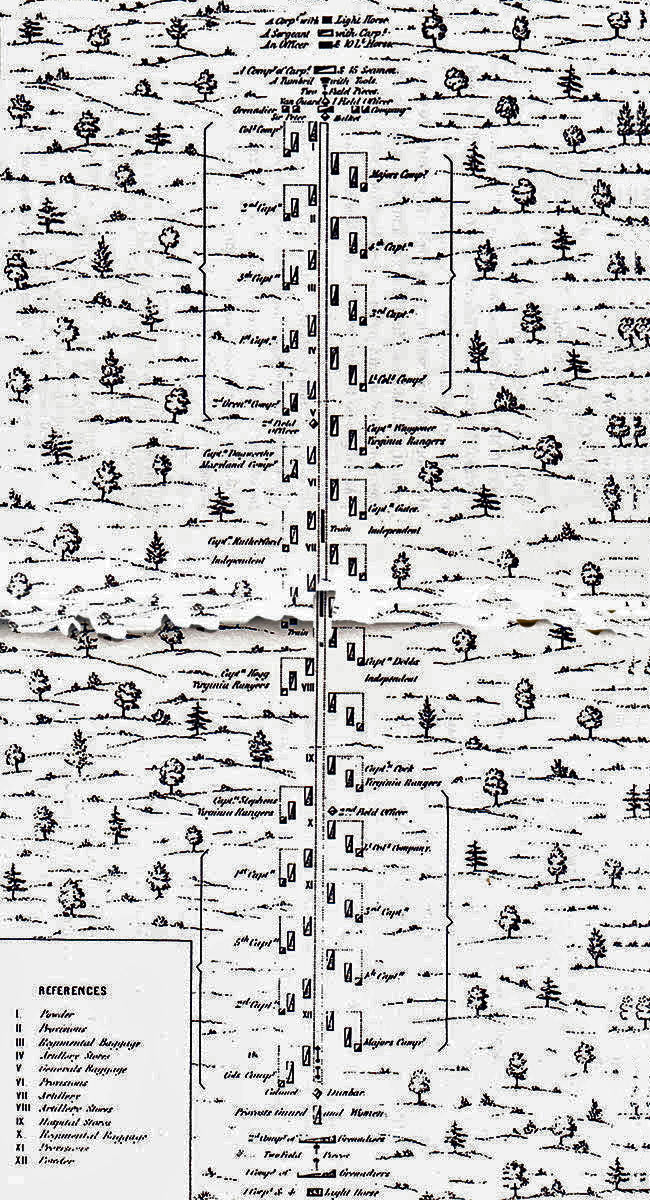

March Plan prepared for Captain Robert Orme’s report to the Duke of Cumberland, submitted in 1756. A number of plans appear in the report, all professionally prepared in England. In fact the plans were not completed in time to accompany the report and were submitted by Orme later

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 7: Braddock’s army at Fort Cumberland in Maryland in May 1755.

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 9: Braddock’s army’s march from Little Meadows to the Monongahela River May to June 1755.

To the French and Indian War index

Map of General Braddock’s march from Fort Cumberland to Fort Duquesne on the Monongahela River, May to July 1755, showing A Spendlow’s Path and camps at 1 Grove 2 Martin’s 3 Little Meadows 4 Laurel 5 Bear 6 Great Crossing 7 Scalping 8 Steep Bank 9 Spring 10 Gist’s 11 Stewart’s 12 Main Crossing 13 Terrapin 14 Jacob’s 15 Salt Lick 16 Hillside 17 Ride 18 Turtle 19 Sugar: Map by John Fawkes

Braddock’s units at Will’s Creek on 8th June 1755:

General Braddock made a return of his troops on 8th June 1755 to Colonel Robert Napier, Adjutant to the Duke of Cumberland. These are the particulars:

British Regular Troops:

44th Regiment of Foot: 33 officers, 5 staff (surgeon, chaplain etc), 30 sergeants, 20 drummers and 770 rank and file.

48th Regiment of Foot: 34 officers, 5 staff, 30 sergeants, 20 drummers and 684 rank and file.

Captain John Rutherford’s New York Independent Company: 4 officers, 1 surgeon, 3 sergeants, 2 drummers and 91 rank and file.

Captain Horatio Gates’ New York Independent Company: 4 officers, 1 surgeon, 3 sergeants, 2 drummers and 91 rank and file.

Captain Paul Demeré’s South Carolina Independent Company: 4 officers, 4 sergeants, 2 drummers and 100 rank and file.

Sir Peter Halkett’s 44th Regiment of Foot: one of General Braddock’s two regiments of foot on his march to the Monongahela in 1755

Provincial Units:

Captain Robert Stewart’s* Troop of Light Horse: 3 officers, 2 sergeants, 33 rank and file.

Captain George Mercer’s* Company of Carpenters: 3 officers, 3 sergeants, 1 drummer and 42 rank and file.

Captain William Polson’s* Company of Carpenters: 3 officers, 3 sergeants, 1 drummer and 50 rank and file.

Captain Adam Stevens’* Company of Virginia Rangers: 3 officers, 3 staff (adjutant, quartermaster and surgeon), 3 sergeants, 1 drummer and 53 rank and file.

Captain Peter Hogg’s* Company of Virginia Rangers: 3 officers, 3 sergeants, 1 drummer and 42 rank and file.

Captain Thomas Waggoner’s* Company of Virginia Rangers: 3 officers, 3 sergeants, 1 drummer and 53 rank and file.

Captain Thomas Cocke’s Company of Virginia Rangers: 3 officers, 3 sergeants, 1 drummer and 47 rank and file.

Captain William Perronée’s* Company of Virginia Rangers: 3 officers, 3 sergeants, 1 drummer and 52 rank and file.

Captain John Dagworthy’s Company of Maryland Rangers: 3 officers, 1 surgeon, 3 sergeants, 1 drummer and 53 rank and file.

Captain Edward Brice Dobbs’ Company of North Carolina Rangers: 3 officers, 1 surgeon, 3 sergeants, 1 drummer and 72 rank and file.

(* These company commanders were all officers in the Virginia Regiment at Fort Necessity in June 1754 as were Lieutenants Carolus Spiltdorf and Walter Stuart of the Virginia Companes.)

Royal Regiment of Artillery:

Captain Robert Hind: 6 officers, 1 surgeon, 2 sergeants, 8 bombardiers, 1 drummer and 41 gunners.

1 waggon master, 1 master of horse, 2 commissaries, 5 conductors and 12 artificers.

Guns and equipment: 4 twelve pounders, 6 six pounders, 4 eight inch howitzers, 15 coehorn mortars, 16 waggons, 8 powder carts, 2 tumbrils, 2 spare gun carriages, 1 forge and 1 money tumbril.

Staff:

Deputy Quartermaster General: Lieutenant Colonel Sir John Saint Clair

ADCs: Captain Robert Orme and Captain Roger Morris

Secretary: William Shirley

Deputy Commissioner of Musters: James Pitcher

Engineers: Captain Patrick Mckellar, Adam Williamson and Harry Gordon

Director of the Hospital: James Napier. Surgeons: John Adair and John Cherrington. Apothecaries: Robert Bristow and William Couche. Surgeons Mates: Matt Leslie, George Tuting and James Campbell. Apothecaries Mates: William Mitchell, Robert Bass and Josiah Williams. Matron: Charlotte Browne

Captain Orme stated that a company of guides was formed from the Native Americans with Braddock’s force. There appear to have been 2 chiefs and 10 braves, of which 3 braves were allocated to each of the 2 regiments, 1 to the General and 3 to the Deputy Quarter Master General. Monacatotha led the Native Americans.

It would seem that James Craik was present with the force as a surgeon. Craik later became Washington’s personal surgeon and was present at his death.

route of General Braddock’s army from Fort Cumberland at Will’s Creek to Little Meadows in May and June 1755

General Braddock was accompanied by Christopher Gist as his guide. Gist was a long standing senior Ohio Company employee having carried out the two explorations of the Ohio country and begun the building of the road along Nemacolin’s Trail for the Ohio Company in 1750 to 1754.

Harry Gordon, the engineer, left a chart of information relating to the march, giving for each day the name of the camp, the distance covered, the work carried out on the road, the nature of the route, the characteristics of the camp and how long the army spent at each camp. Gordon’s particulars are set out for each camp. Feeding refers to grazing for the horses.

The army left Fort Cumberland in 4 groups on different days. Saint Clair’s advance party left Fort Cumberland several days before the rest of the army, and waited for the other groups to catch up at Little Meadows.

Virginian ‘Carpenters’ and British Pioneers clearing the road for General Braddock’s army on the march to the Monongahela in 1755

29th May 1755: First Stage of the March: Fort Cumberland to Grove Camp (subsequently renamed Spendlowe’s Camp):

Engineer Gordon’s entry: From Fort Cumberland to Grove Camp-5 miles- A great deal of cutting and digging and some blowing (blasting rocks)-The hill very rough, its rise quick, its fall quick and narrow, the rest tolerable-camp open, moist, good feeding, plenty of tolerable water-2 days.

The march began with Saint Clair and Chapman’s advance party leaving Fort Cumberland on 29th May 1755 to begin work on the road and set up the first camp, Grove Camp (subsequently renamed Spendlowe’s Camp after Lieutenant Spendlowe Royal Navy discovered the alternative easier route around the north of the mountain). The route was up the mountain behind the fort to the south-west, subsequently called Will’s Mountain, and down the far side. The mountain side was forested and rocky. On this first day the army found out just how hard this journey was going to be. Wagons had to be winched up the mountainside in many places and winched down the far side.

The Seaman recorded: “A detachment of 600 men marched towards Fort Du Quesne under the command of Major Chapman with 2 field pieces and 50 wagons with provisions. Sir John St Clair, 2 Engineers, Mr Spendlowe and 6 of our people to cut the road and some Indians went away likewise.”

Captain Cholmley of the 48th Regiment was one of the officers in this party. His batman recorded: “marched 7 miles in 8 hours. Very bad roads obliged to halt every 100 yards and mend them. As soon as at camp working party sent out to cut the roads and a covering party. Working 200 men, covering 100 men.”

Captain Robert Orme wrote in his journal: “This detachment of six hundred men commanded by Major Chapman marched the 30th of May at daybreak (Orme gave the wrong day), and it was night before the whole baggage had got over a mountain about two miles from the camp. The ascent and descent were almost a perpendicular rock; three wagons were entirely destroyed, which was replaced from the camp; and many more were extremely shattered. Three hundred men (of whom the General had formed a company), had already been employed several days upon that hill.”

Orme wrote his journal after the campaign as part of his effort to restore his reputation and justify the conduct of the expedition to the Duke of Cumberland. In spite of his hyperbole it is clear that the first day was an ordeal for those involved and this part of the route very difficult for the army’s transport.

The beginning of the ascent up Will’s Mountain in later times. The road cut by Braddock’s army is by the fence

30th May 1755: Second Stage of the March: Grove Camp to Martin’s Camp:

Engineer Gordon’s entry: to Martin’s-5 miles-A great deal of cutting, digging and bridging- One mile level but swampy, 2 ½ miles very rough and steep, the rest tolerable but here and there swampy-camp open, dry, very good feeding, fine water-1 day.

On 30th May 1755 Saint Clair and Chapman’s advance party moved on from Grove Camp to Martin’s Camp, crossing the Great Savage Mountain. This day was as bad as the previous. Where the ground was level it was swampy making it necessary to build bridges or causeways.

Captain Cholmley’s batman recorded: “Marched at 6am. Party that cut roads marched at 4am. Marched to 8pm. Only 3 miles. Delayed by great quantity of wagons and the roads being all to cut.”

Daniel Boone: picture by Alonzo Chapell: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The Seaman (still at Fort Cumberland) recorded: “Arrived here a company from North Carolina under the command of Captain Dobbs.”

Dobbs was the son of the governor of North Carolina. His company of North Carolina Rangers brought a number of wagons, one of which was driven by Daniel Boone, later a renowned frontiersman.

George Washington recorded in a memorandum: “Upon my return from Williamsburg I found Sir John St Clair with Major Chapman and a detachment of 500 men were gone on to the Little Meadows in order to prepare the roads, erect a small fort and to lay a deposit of provisions there.”

31st May 1755: Third Stage of the March: Martin’s Camp to Little Meadows:

Engineer Gordon’s entry: Little Meadows-10 Miles-A great deal of cutting, digging and bridging and a great deal of blowing (rock blasting)-4 miles up and down the ridge very rough and steep, the rest for about 5 miles tolerable, 1 mile rough and a hard pinch-camp inclosed with an abates, dry, fine feeding, good water scarce-3 days.

On 31st May 1755 Saint Clair and Chapman’s advance party marched to Little Meadows, where they built a camp defended by an abattis. That a distance of 10 miles was covered, double the distance on each of the previous two days, indicates that this day was easier, although steep mountain sides had to be negotiated as on the previous days with waggons winched up and down. Saint Clair and Chapman’s advance party waited at Little Meadows Camp for Braddock and the main army to catch up.

Captain Cholmley’s batman recorded: “3 miles to ground. Provisions and cooked them working party to cut roads up a large mountain. Covering party to guide them.”

1st June 1755:

Saint Clair and Chapman’s advance party remained at Little Meadows, sending a detachment to work on the next section of road.

The Seaman at Fort Cumberland recorded: “We hear the detachment is got 15 miles. Mr Spendlowe and our people returned.”

The summit of Will’s Mountain at a later date

2nd June 1755:

On 2nd June 1755 Saint Clair and Chapman’s advance party remained at Little Meadows, again sending a detachment to work on the section of road to Laurel Camp.

At Fort Cumberland various officers were examining the difficult section of road built straight up what would be known as Will’s Mountain, behind the fort. Lieutenant Spendlow RN found an alternative and easier route around the north of the mountain leading from a path along Will’s Creek.

The Seaman (at Fort Cumberland) recorded: “Colonel Burton, Captain Orme, Mr Spendlowe and self went out to reconnoiter the road. Mr Spendlowe left us and returned to camp at 2pm and reported he had found a road to avoid a great mountain. In the afternoon we went out to look at it and found it would be much better than the old road and not above 2 miles about.”

Orme recorded this event: “The General reconnoitred this mountain and determined to set the engineers and three hundred men at work upon it, as he thought it impassable by Howitzers. He did not imagine any other road could be made, as a reconnoitring party had already been to explore the country; nevertheless, Mr Spendelowe, Lieutenant of the Seamen, a young man of great discernment and abilities, acquainted the General, that, in passing that mountain, he had discovered a Valley which led quite round the foot of it. A party of a hundred men, with an engineer, was ordered to cut a road there, and an extreme good one was made in two days, which fell into the other road about a mile on the other side of the mountain.”

3rd June 1755:

Parties from Little Meadows continued to work on the next section of road.

Captain Cholmley’s batman at Little Meadows recorded: “10pm night before alarmed by several shots. Stood to until 2am after that laid on arms all night. Then marched 6 miles with working party as usual.”

The Seaman at Fort Cumberland recorded: “This morning Mr Engineer Gordon and 100 men began working on the new road from camp and Mr Spendlowe and self with 20 of our men went to the place where the new road comes into the old one and began to clear away and completed a mile today.”

Allegheny Mountain in later times

4th June 1755:

As on previous days the main advance party remained at Little Meadows while the working parties reached the site of Laurel Camp.

Captain Cholmley’s batman recorded: “Halted by River Laurel received provisions and after cooking them party went to work. Hunter brought back bear killed a wolf.”

The Seaman (working on the new road behind Will’s Mountain) recorded: “1 midshipman and 20 men cleared ¾ of a mile.”

Great Savage Mountain in later times

5th June 1755:

The working parties at Laurel Camp returned to Little Meadows.

Captain Cholmley’s batman recorded: “March to Little Meadows 4 miles, very bad roads over rocks and mountains almost impassable. 10 hours march. Hunter shot 2 elks and a bear and a deer and wounded two more. Dined on bear and rattle snake.”

On 5th June 1755 the Seaman at Fort Cumberland recorded: “We went out as before and at noon Mr Spendlowe and I went to the other party to mark the road for them but at 1 it came to blow rain thunder and lighten so much that it split several tents and continued so until night when we returned to the camp.”

6th June 1755:

Captain Cholmley’s batman at Little Meadows recorded: “halted and unloaded all the wagons and sent them to Ft Cumberland. 300 men went as guards. Working party clearing ground around the Meadows. Dined on snake and bear and deer.”

The Seaman at Fort Cumberland recorded: “We went out as usual and at 2pm completed the road and returned to camp. This evening I was taken ill.”

General Braddock’s orders at Fort Cumberland directed: “Sir Peter Halkett’s regiment to march tomorrow morning……Captain Gates’s and the other companies of provincial troops to march on Sunday morning with the whole park of artillery. Major Spark’s general court martial is dissolved: Michael Shelton and Caleb Sary, soldiers of Captain Brice Dobbs’s company of Americans (the North Carolina company) tried and sentenced for desertion to receive 1,000 lashes each. …… No soldier’s wife allowed to march with a horse.”

7th June 1755:

Captain Cholmley’s batman at Little Meadows recorded: “working party to clear camp and build houses over provisions. Received 5 days provisions. 5 men of Carolina companies intended to depart after receiving provisions but were apprehended by one informing. Dined on bear.”

Sir Peter Halkett’s brigade reached the First Camp, Grove or Spendlowe’s.

The Seaman recorded: “A rainy day with thunder and lightening. Sir Peter Halkett and his brigade marched with 2 field pieces and some wagons with provisions. A midshipman and 12 of our people went to assist the train.”

George Washington wrote in a letter to John Washington: “… As I have wrote to you twice since the first inst. I shall only add that the difficulties arising in our march from having a number of wagons will I fear prove insurmountable unless some scheme can be fallen upon to retrench the wagons and increase the number of bat horses which is what I recommended at first and I believe is now found to be the most salutary means of transporting our provisions and stores to Ohio….”

8th June 1755:

Captain Cholmley’s batman at Little Meadows recorded: “men to work clearing the camp. Some of our Indians advanced 5 miles in front of the camp came up with many French Indians roasting deer. Indians returned to collect party of Captain, Lieutenant, Ensign and two drums and 50 privates. Did not catch the Indians. 4 deserters given 1000, 900 and 2 X 500 lashes. It was thought they would have gone to the French and given them information.”

John Montresor, ensign in the 48th Foot in 1755, son of James Montresor, Braddock’s chief engineer (but not with the Expedition to the Monongahela);

painted in later life by John Singleton Copley

On 8th June 1755 General Braddock wrote from Fort Cumberland to Colonel Robert Napier, Adjutant to the Duke of Cumberland, saying: “… … I hope to leave this place to morrow with a less Quantity of provisions than I propos’d from the Disappointment of the Waggons and Weakness of the Horses. To remedy as much as possible this Inconvenience I have sent forward a strong Detachment with a large Convoy of provisions to be lodg’d upon the most advantageous spot of the Alliganey Mountains with directions for the Waggons to return with a proper Escort. …..Nothing can well be worse than the Road I have already pass’d and I have an hundred and ten miles to march thro’ an uninhabited Wilderness over steep rocky Mountains and almost impassable Morasses. From this Description, which is not exaggerated you conceive the difficulty of getting good Intelligence, all I have is from Indians, whose veracity is no more to be depended upon that of the Borderers here; their Accounts are that the Number of French at the Fort at present is but small, but pretend to expect a great Reinforcement; this I do not entirely credit, as I am very well persuaded they will want their Forces to the Northward. As soon as I have join’d the Detachment, who have been seven days making a Road of twenty four Miles, I shall send people for Intelligence, who I have reason to believe I can confide in. I have order’d a Road of Communication to be cut from Philadelphia to the Crossing of the Yanghyandhain, which is the Road we ought to have taken, being nearer, and thro’ an inhabited and well cultivated Country, and a Road as good as from Harwich to London, to some Miles beyond where they are now opening the new Road…….”

The order books for Fort Cumberland (General Braddock’s) and Halkett’s show that there was a trawl for soldiers experienced in driving wagons and handling pack horses.

9th June 1755:

Lieutenant Colonel Burton left Fort Cumberland with Gate’s Independent Company and the remaining Ranger Companies.

At Little Meadows Captain Cholmley’s batman recorded: “Went to work clearing wood and laying it round the camp for a breast work. Soldier tried for sleeping on sentry. Good character so forgiven. All the volunteers and Indians advanced to Great Meadows and proposed returning in 4 days.”

10th June 1755:

Captain Cholmley’s batman at Little Meadows recorded: “Men worked at breast work. Indian from the French who said French marching from Great Meadows to engage us.”

Captain Orme wrote that Colonel Dunbar left Fort Cumberland with the 48th and a proportion of the baggage and the General left Fort Cumberland and joined the whole at Spendelowe’s Camp 5 miles from the Fort.

The Seaman recorded: “The director of the hospital came to see me in camp and found me so ill of a fever and flux that he desired me to stay behind so I went into the hospital and the army marched with the train etc and as I was in hopes of being able to follow them in a few days I sent all my baggage with the army and in the afternoon the General his aides de camp etc with a company of Light Horse marched. The last division of his Majesty’s forces marched from Will’s Creek or Fort Cumberland with General Braddock and his ADC etc.”

The Officer recorded: “All the remaining troops marched from Fort Cumberland: 1500 men. A detachment of 600 and 2 engineers having marched some days before to clear the roads. The march attended by many difficulties owing to the road and carriages being bad and although the line of march was only intended to be 2 ½ miles in extent, frequently twice that. This was a circumstance impossible to be helped, accidents occasioning many halts in different parts of the line.

Necessary to lighten the carriages. Sent back 2 six pounders. Train now 4 twelve pounders; 4 six pounders, 4 Howitzers and 15 coehorns with 300 rounds for each and 3 months provisions for 2000 men. Everything sent away to Ft Cumberland.”

General Braddock’s orders directed: “…all officers of the line to be at the general’s tent tomorrow morning at 11am. No fires on any account within 150 yards of the road on either side. Any person acting contrary very severely punished. All the wagons tomorrow morning to be drawn up as close as possible as soon as Chapman’s wagons have closed up to the rear of the artillery that detachment to join their respective corps. 48th to encamp tomorrow morning upon the left of the whole according to the line of encampment.”

11th June 1755:

Captain Cholmley’s batman at Little Meadows recorded: “Work as usual. Indians and Volunteers returned to camp. No French seen. Duty here is excessive hard, having only one night in bed. The day of guard go to work, either on guard or working. Only salt meat and water to live on and not sufficient of that.”

Braddock’s main force was now at Grove or Spendlowe’s Camp. It was apparent that the transport arrangements were wholly inadequate. There were too few carrying horses and most of these were too weak to carry the expected load of 2 hundredweight, only managing 1 hundredweight. There were no horses large enough to pull the wagons brought from England to carry the gunpowder, referred to as ‘the King’s Wagons’, when loaded. These wagons were emptied and returned to Fort Cumberland, their loads transferred to smaller country wagons. The loads of all the wagons were reduced to accommodate the weak and ill-favoured horses that had been supplied to Braddock.

General Braddock assembled all the officers of the line at his tent at 11am (this would be the officers of the 44th and 48th. The officers of the artillery and independent companies may also have been included).

Braddock reminded them of the crisis due to the lack of horses and the poor condition of those they did have. Braddock asked his officers to return as much of their baggage as possible to Fort Cumberland and to hand over as many of their private horses as possible for the army’s use. Braddock said that he and his staff were contributing 20 such horses. Captain Orme reported: “This had such an effect, that most of the Officers sent back their own, and made use of Soldiers tents the rest of the Campaign, and near a hundred able horses were given to the publick service.”

Captain Orme recorded that, at a Council of War, it was agreed to send back to Fort Cumberland 2 six pounder canon, 4 coehorns, powder and stores, which cleared nearly 20 wagons. All the King’s wagons were sent back as too large for the horses. A day was spent moving stores around. 1 company was sent to cover the road building in Pennsylvania. 50 of the worst men from the Independent and Ranger companies were sent back to Fort Cumberland. All but 2 women per company were sent back. The extent of the camp with the wagons closed up was now less than half a mile.

12th June 1755:

Captain Cholmley’s batman at Little Meadows recorded: “Work on breast work. I went to the Grand Army bought 6 loaves and some mutton.”

Colonel Halkett’s orders directed: “….Women to be sent back to the fort march with Capt Hoggs’ detachment.”

Friday, 13th June 1755:

Captain Cholmley’s batman at Little Meadows recorded: “Work on the roads with covering party. Expect French Indians to attack. Dined on snake and bear.”

Braddock’s main force marched from Grove or Spendlowe’s Camp to Martin’s Camp.

Little Meadows in later times

Captain Orme recorded: “took 2 days to reload the wagons. Marched to Martin’s Plantation 2 miles from Spendlowe. 1st Brigade got there that night. 2nd Brigade could not get up until the next day the road being excessively mountainous and rocky obliged the General to halt.”

The Officer recorded: “General at 4am and soon on march. This day’s march closer than the former but still was tedious and with some accidents; we marched 6 miles to George’s Creek and halted next day.”

Charlotte Browne, on the road from Alexandria to Will’s Creek, recorded: “The drum beat and awaked me At 3 we marched but I was so ill I could not hold up my head. 3 of the wagons broke down at 4 in the afternoon. Mr Bass (Apothecary’s Mate) came to meet us and gave me some letters from England. At 6 we came to Fort Cumberland, the most desolate place I ever saw. Went to Mr Cherrington who received me kindly, drank tea and then went to the Governor’s to apply for quarters. I was put in a hole that I could see day light through every log and a port hole for a window: which was as good a room as any in the fort.”

On 13th June 1755 Sir John Saint Clair wrote to Colonel Robert Napier, Adjutant to the Duke of Cumberland, from the Camp at Little Meadows, and said: “….The Situation I am in at present puts it out of my power to give you a full description of this Country; I shall content myself with telling you that from Winchester to this place is one continued track of Mountains, and like to continue so for fifty Miles further…….. In this Situation we never cou’d have subsisted our little Army at Will’s Creek, far less carried on our Expedition had not General Braddock contracted with the People in Pennsylvania for a Number of Waggons, which they have fulfilled; by their Assistance we are in motion, but must move slowly until we get over the Mountains. I cou’d very easily forsee the diffcultys we were to labour under from having the Communication open only to Virginia, which made me anxious of having a Road cut from Pennsylvania to the Yaugheaugany; I wrote to Govr Morris the 14th of Febry on this Head, notwithstanding of which, that Road has not been set about till very lately. The last Report that I had of it, was, that it wou’d be finished in three Weeks hence; the two Communications will join about forty Miles from hence, but it is not fixed on which side of the Yaugheogany.

British sentry fires on a marauding Native American during General Braddock’s march to the Monongahela in 1755

The little knowledge that our People at home have of carrying on War in a Mountaineous Country will make the Expence of our Carriages appear very great to them, that one Article will amount near to £40,000 Stir.

Thus far I do affirm that no time has been lost in pursuing the Scheme laid down in England for our Expedition; had it been undertaken at the beginning from Pennsylvania it might have been carried on with greater Dispatch and less expence: I am not at all surprised that we are ignorant of the Situation of this Country in England, when no one except a few Hunters knows it on the Spot; and their Knowledge extends no further than in following their Game. It is certain that the ground is not easy to be reconoitered for one may go twenty Miles without seeing before him ten yards.

The Commanding General pursues his Schemes with a great deal of vigour and Vivacity; the Disposition he makes will be subject to be changed in this vast tract of Mountains, I mean instead of marching the whole together (the Van Guard excepted) in one Body, he will be obliged to march in three Divisions over the Mountains and join about the great Meadows, fifty two Miles from the fort. The General is bent on marching directly to Fort Du Quesne, he is certainly in the right in making his Dispositions for it: But it is my opinion he will be obliged to make a Halt on the Monongahela or Yaughangany until he gets up a Second Convoy, and until the Road is open from Pensylvania, which the Inhabitants will not finish unless they are covered by our Troops.

………I am at this place with 400 Men as a Van Guard, and to cut the Roads, I was not able to reach this Ground till the 8th Day, ‘tho only 20 Miles from Will’s Creek, it is certain I might have made more dispatch but I was charged with a Convoy of 50 Waggons. The Roads are either Rocky or full of Boggs, we are obliged to blow the Rocks and lay Bridges every Day; What an happiness it is to have wood at hand for the latter!

One of our Indians who left the french Fort the 8th Inst, tells me that there are only 100 french & 70 Indians at that place; that they are preparing to set out the Day after to dispute the passage of the Mountains. I have seen nothing of them as yet, nor do I expect that they will come so far from home. …. “(received by Colonel Robert Napier in London on 29th August 1755)

Saturday 14th June 1755:

Captain Cholmley’s batman at Little Meadows recorded: “Work on breast work and clearing camp.”

Braddock’s main force was at Martin’s Camp.

The Officer recorded: “Halted this day.”

George Washington wrote to Samuel Washington: “I am excessively hurried therefore have not time to be particular in informing you of the occurrences that have or may happen…”

Colonel Halkett’s orders directed: “…… The number of carriages to be equally divided. Sir Peter Halkett and his field officers with the troops of the first brigade to take under their care half the carriages and to their officers order their men to assist the wagons when any pinch of a hill or difficulty that may append. Col Dunbar and his field officers with the troops of the second brigade is to act in the same manner with the remaining carriages………..The general to beat tomorrow morning at 4 o’clock when the troops comes to Savage River, the servants, batmen, waggoners and horse drivers must take particular care to prevent their horses eating of Laurel as it is certain death to them. His Excellency General Braddock has been pleased to appoint Ensigns Daniel Disney, Quintin Kennedy, Robert Drummond to be Lieutenants in Sir Peter Halkett’s regiment of foot as also Messrs Thomas Gamble, James Allen, Ely Dagworthy to be ensigns in the said regiment and are to be obeyed as such.

Upon the beating of the general tomorrow morning two companies from the right of Sir Peter Halkett’s regiment to strike their tents and march as an escourt to the carrying horses of the army. The commanding officer to apply to Captain Morris for his orders.”

15th June 1755:

Captain Cholmley’s batman at Little Meadows recorded: “Work on breast work. 2 companies of Halkett’s came in with 200 horses laden with flour and bread.”

Captain Orme recorded: “The Line moved at 5am. 12am before all carriages had got upon a hill ¼ mile from the front of the camp. Necessary for ½ men to assist the carriages while other ½ posted for security. Passed the Allegheny Mountain which is a rocky ascent of more than two miles, in many places extremely steep; its descent is very rugged and almost perpendicular; in passing which we entirely demolished three wagons and shattered several. At the bottom passed Savage River, an insignificant stream at this time. Last water that empties into the Potomac, deep wide and rapid in winter. 1st Brigade encamped about 3 miles from this place. Near was another steep ascent which the wagons were 6 hours in passing. Line sometimes 4 or 5 miles.”

The Officer recorded: “marched within 4 miles of Little Meadows.”

Monday 16th June 1755:

Captain Cholmley’s batman at Little Meadows recorded: “Work on breast work. Most of Grand Army arrived. A ranger out shooting meets Indians shooting deer returns and reports enemy. Party sent out finds friendly Indians shot 3 deer.”

The Officer recorded: “General at 3am and although the distance was short 2 very long steep hills hindered the last brigade from reaching the Meadows that day.”

On Tuesday 17th June 1755:

Captain Cholmley’s batman at Little Meadows recorded: “Rest of Grand Army arrived. 600 men went to work on roads with covering party. Expect to march to Great Meadows tomorrow. General Braddock cross to find soldiers building stockade not working on roads.”

The Officer recorded: “2nd Brigade reached Little Meadows. The weather being very hot and water bad it caused many fluxes and fevers among the men.”

Braddock’s whole force was now concentrated at the Camp in the Little Meadows preparing for the next stage of the tortuous march through the mountains and on to Fort Duquesne.

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 7: Braddock’s army at Fort Cumberland in Maryland in May 1755.

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 9: Braddock’s army’s march from Little Meadows to the Monongahela River May to June 1755.

To the French and Indian War index