The battle that saw Frederick the Great escape from overwhelming odds on 15th August 1760

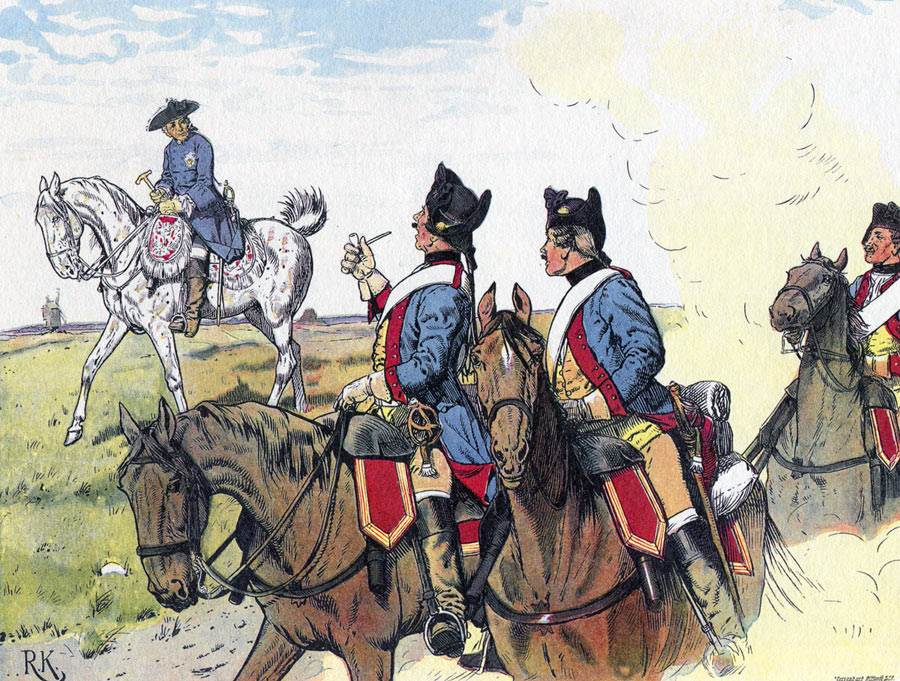

Frederick the Great greeted by Prussian Dragoons on the march: Battle of Liegnitz 15th August 1760 in the Seven Years War: picture by Richard Knötel

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Kunersdorf

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Torgau

Battle: Liegnitz

Date of the Battle of Liegnitz: 15th August 1760.

Place of the Battle of Liegnitz: On the bank of the Katzbach River in Northern Silesia.

War: The Seven Years War.

Contestants at the Battle of Liegnitz: Prussians against an Imperial Austrian Army comprising the various nationalities that made up the Austrian Army (Austrians, Hungarians, Bohemians, Silesians, Croats, Italians and Moravians).

Generals at the Battle of Liegnitz: King Frederick II of Prussia, known as Frederick the Great, commanding the Prussian Army against Marshal Daun commanding the Austrian Army. The section of the Austrian army principally involved in the battle was the contingent commanded by General Loudon.

Size of the Armies at the Battle of Liegnitz: Prussians: 30,000 men and 74 heavy guns. Austrians: the main army commanded directly by Daun 66,000 men: General Loudon’s contingent 25,000.

Uniforms and equipment at the Battle of Liegnitz: The Prussian infantry and artillery wore a dark blue coat turned back at the lapels, cuffs and skirts with britches and black thigh length gaiters. From cross belts hung an ammunition pouch, bayonet and ‘hanger’ or small sword. Headgear for the line companies was the tricorne hat with the receding front corner bound with white lace. Grenadiers wore the distinctive mitre cap with the brass plate at the front. Fusilier Infantry Regiments and gunners wore the smaller version of the grenadier cap.

The infantry carried the musket as their main weapon. The single shot musket could be loaded and fired by a well trained soldier between 3 and 4 times a minute. During the course of his wars Frederick introduced the iron ramrod and then the reversible ramrod which increased the efficiency of his infantry, the wooden ramrod being liable to break in the stress of battle.

Prussian Infantry Regiment Anhalt-Bernberg No 3: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

The Prussian infantry regiment was based on the cantonment, with soldier joining their local regiment. Soldiers were released for key agricultural times such as sewing and harvesting. In the autumn reviews were conducted of all regiments to check that each regiment was up to the required standard. Each year certain regiments were selected to conduct the review at Potsdam under the eye of the King. Officers whose soldiers were considered by Frederick not to be of a sufficient standard were subjected to a public tongue lashing and in extreme cases dismissed on the spot.

The efficiency of the Prussian regiments at drill enabled them to move around the battlefield with a speed and manoeuvrability that no other European Army could equal.

Heavy cavalry of the period comprised cuirassiers, whose troopers wore steel breastplates, and dragoons. The main form of light cavalry were the regiments of hussars. The Austrian hussars were Hungarian and the genuine article while the hussars of other armies were given the same dress as Hungarian hussars and expected to perform to similar standards.

Prussian Königs Leibgarde (the regiment lost 24 officers and 475 men in the battle): picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

The Prussian cuirassiers wore a white coat, steel cuirass, white britches and thigh boots. The headgear was the tricorne hat. Dragoons wore a light blue coat. Weapons were a heavy cavalry sword and single shot flintlock carbine.

The light cavalry arm was provided by the Prussian Hussar regiments. Frederick found the Prussian Hussars as inadequate for their role as the heavy cavalry regiments. Following Mollwitz and in particular after the First Silesian War the hussars were re-organised and re-trained to provide a first class scouting and light cavalry service. Frederick found in Colonel von Zieten the ideal officer to implement the improvements in the hussar regiments. The Prussian Hussars wore the traditional hussar dress worn by the original Hungarian Hussars of tunic, britches, dolman (slung jacket), busby (fur hat) with bag, sabretache (leather wallet on straps) and curved sword.

The Austrian infantry wore white coats with lapels, cuffs and skirts turned back showing the regimental lining colour. Headgear was the tricorne hat for line infantry and bearskin cap for grenadiers. The infantry weapons were musket, bayonet and hanger small sword. Heavy cavalry wore white coats and hats as for the infantry and were armed with a heavy sword and carbine. The Austrian army contained a large number of irregular units such as the Pandours from the Balkans who wore their ethnic dress without uniformity. Hungarian Hussars provided the light cavalry arm. These Hussars were dressed as described for the Prussian Hussars, were considered to be little more than bandits but were highly effective in all the roles required of light cavalry.

Prussian Husaren-Regiment von Wartenberg No 3: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

The artillery of each army was equipped with a range of muzzle loading guns. The Prussian Artillery was considerably more efficient at manoeuvring on the battle field. In the changes implemented by Frederick after the First Silesian War horse artillery was introduced to support the Prussian cavalry.

Background to the Battle of Liegnitz:

1759 had seen severe reverses for Frederick; the Battle of Kunersdorf against the Russians on 12th August and the capture of General Fink’s Prussian force of around 12,500 men at Maxen in Saxony by Daun’s army on 20th November. The 1760 campaign season began with the capture of Fouqué’s Prussian force of 8,000 men after suffering 1,000 casualties at the hands of General Loudon on 23rd June.

On 3rd July 1760 Frederick set off from Gross-Dobritz, where he had wintered with his army, for Silesia. He then received information that Daun’s Austrian army would reach Silesia before him. Frederick turned back into Saxony and determined on an attempt to recover the Saxon capital of Dresden, surrendered to the Austrians by Count Schmettau after the disaster of Kunersdorf the previous year. Frederick reached Dresden with his army on 13th July 1760.

Frederick subjected Dresden to a damaging artillery bombardment which achieved little. There were further manoeuvrings against the city before Daun arrived with his army from Silesia on the Elbe River and made contact with the Austrian garrison in the city. Frederick was compelled to pull back.

Prussian Füsilier-Regiment Neuwied No 41: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

During the withdrawal of the Prussian batteries out of reach of the Austrians a force of Prussian infantry was broken by a sudden attack. The Regiment of Alt-Bernberg, one of Frederick’s most reliable formations, broke and ran. Frederick was so enraged that he ordered the Bernberg regiment to be deprived of its swords and the officers and NCOs to be stripped of their lace embellishments.

Frederick lingered outside Dresden hoping that Daun would come down into the plain and give battle. On 29th July 1760 the Austrian General Loudoun captured the important Silesian arsenal of Glatz and advanced to threaten the Silesian capital of Breslau. Prince Henry, Frederick’s brother, was forced to leave his position east of the Oder River, cross to the west bank and relieve Breslau. This move left Saltykov with his Russian army free to advance from Posen in Poland to the Oder River and to cross into Silesia. Saltykov detached a corps of 25,000 men commanded by General Chernyshev with orders to cross the Oder River and join the Austrians. There was a clear danger that the Russian and Austrian armies would combine, the strategic aim of the Austrian and Russian Empresses throughout the war. Frederick was forced to march east into Silesia to prevent this combination coming about.

As soon as Frederick left the area of Dresden Daun set off in pursuit. The Prussians rested at Bunzlau, a pause which enabled Daun to pass the Prussians and join up with Loudoun’s force, creating an army more than double the size of Frederick’s. Frederick intended to march to the Schweidnitz-Breslau area to combine with his brother, Prince Henry’s, army. In order to do so Frederick had to evade the Austrian army which marched in parallel with the Prussians along the banks of the Katzbach River.

Winner of the Battle of Liegnitz: The Prussians.

Account of the Battle of Leignitz:

Frederick made attempts to evade the Austrians, cross the Katzbach and march to Breslau. He was unable to do so. On 14th August 1760 the Prussians were encamped on the heights to the West of the town of Leignitz overlooking the Katzbach. Frederick made the decision to abandon his attempt to cross the Katzbach in that area, to march down the northern, left bank, of the Katzbach to the town of Parchwitiz, near to its confluence with the Oder River, and attempt a crossing there.

The Prussian army began the march on the night of 14th August 1760. As was so frequently the practice the Prussians left their campfires burning to mask the move. The Prussian piquets remained in place to prevent any early discovery of the ruse. A drunken Irish officer, Captain Wise, who had been dismissed the Austrian service, arrived in the Prussian camp and warned Frederick that the Austrian army was on the move to attack him. The form of Daun’s intentions were not clear at this point.

Prussian Grenadier Battalion von Rath No 5: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

Daun’s elaborate plan required Loudon’s force, which with 24,000 men was approximately the same size as the Prussian army, to cross the Katzbach to the East of Leignitz and cut off Frederick’s escape route while Daun crossed the Katzbach in the area of Dohnau and attacked the Prussian camp. A further force commanded by General Lacy was to circle round from the North and attack the Prussian camp in the rear, cutting off any retreat in that direction. The aim of Daun’s plan was to trap the Prussians on the western side of the Schwartzwasser and force the surrender of the whole army with its king.

After moving out of their camp the Prussians halted for the remainder of the night on the high ground to the East of Liegnitz and the Schwarzwasser. The focus of the Prussian position was the Reh-Berg hill overlooking the village of Panten. Meanwhile the Austrians were on the move. Loudon crossed the Katzbach and was advancing west along the Leignitz road. Austrian light troops were demonstrating from the far side of the Katzbach in the area of Leignitz with the aim of diverting the Prussians from Daun’s powerful force approaching from Dohnau where it was crossing the Katzbach. Lacy was approaching with his force from Arnsdorf to the North of Leignitz.

Prussian Horse Artillery: Battle of Leignitz on 15th August 1760 in the Seven Years War: print by Adolph Menzel

Due to the Prussian move Loudoun’s force was the first to make contact. Major Hundt of the Zieten Hussars was patrolling the road in advance of the Prussian march to the East when he encountered Loudoun’s force marching down the road towards him. It was not yet dawn. Hundt rode hard to the Prussian encampment and found the King. Frederick asked “What is going on?” Hundt said “As God is my witness the enemy is here.” Frederick called for his horse and began the task of organising his army in the face of this unexpected assault. The Prussian deployment began at around 3am.

General Zieten was given the task of holding the ground above the Schwartzwasser and Leignitz facing west against Daun with a substantial portion of the army while Frederick fought off Loudoun. It had to be expected that Daun would attack across the Schwarzwasser with a substantial number of men and so Zieten’s force comprised around two thirds of the Prussian army.

Preparing to face the swiftly advancing Austrians commanded by Loudon Frederick positioned a battery of 12 pounder guns on the Reh-Berg with infantry holding each flank of the hill.

Both sides were taken by surprise to encounter their enemy at this point. Frederick did not expect any Austrians to have circled round and come up in his rear. Loudoun believed that the Prussians were still in their camp on the far side of the Schwartzwasser. But Loudoun was not the sort of general to shirk a battle, particularly once it had been joined.

The Prussians were still forming their line when Loudoun’s right hand column comprising a powerful cavalry force charged Frederick’s left near the village of Humeln. Initially successful against the Zieten Hussars and the Krockow Dragoons the Austrians were driven back by a charge of Prussian Cuirassiers and the infantry regiment of Alt-Bernberg.

Nearer the bank of the Katzbach the Austrian infantry attacked up the Reh-Berg and along the Leignitz road. The fire of the 12 pounder battery and the Prussian infantry brought the Austrians to a halt and a savage counter-attack along the Prussian line drove the Austrians down the hill and back through Panten.

While their infantry fell back the Austrian cavalry charged the Prussians and inflicted heavy casualties on a number of regiments before drawing off and re-crossing the Katzbach to the south bank. Although clearly defeated Loudoun extracted his force in good order.

Frederick the Great in the camp at Leignitz 15th August 1760 before the battle in the Seven Years War: picture by Carl Röhling

On the west bank of the Schwartzwasser Daun’s force, the largest part of the Austrian army and the force that Daun had expected to deliver the main blow in eliminating the Prussian army, was slow in crossing the Katzbach at Dohnau and forming up for the attack on the Prussian camp. Before Daun was in place Lacy’s force arrived from its circle around to the north of the Prussian camp and took up positions along the Schwartzwasser. Lacy tried to find a suitable place to cross the river and attack Zieten on the rising ground beyond the Schwartzwasser. Some of Lacy’s cavalry on his extreme left managed to find a crossing point at Rüstern, but were driven back. Loudoun’s men were left unsupported by the rest of the Austrian army during their frenzied attack on Frederick’s line.

Casualties at the Battle of Liegnitz: Prussian losses: 3,394 men killed, wounded and captured.

Austrian losses: 8,500 men killed, wounded and captured and 80 guns lost.

Aftermath to the Battle of Liegnitz:

The most important and immediate effect of the Battle of Leuthen was that Chernyshev with his Russian force on hearing the news of the battle and that Frederick was hurrying towards him crossed back to the east bank of the Oder River. Daun turned away and took his army into the South of Silesia. The juncture of the Russian and Austrian armies was thwarted and the threat to the Silesian capital of Breslau lifted.

Anecdotes from the Battle of Liegnitz:

- The Battle of Leuthen was fought when Frederick and the fortunes of the Prussian state were at a low ebb. The battle restored Prussian morale and acted as a corresponding dampener on the expectations of the Austrians and Russians in beating Frederick. The battle restored the confidence of the Prussian army in their king, so disastrously undermined by the Battles of Hochkirch, Kunersdorf and Maxen.

- Immediately after the Battle of Liegnitz a group of private soldiers from the Alt-Bernberg Regiment rushed up to Frederick and petitioned him for the restoration of their regimental embellishments in the light of their outstanding conduct during the battle. The embellishments had taken from them by Frederick due to the regiment’s misbehaviour at Dresden in the previous month . Frederick agreed to do so.

- Frederick’s bombardment of Dresden put a significant dent in his reputation. It was seen as a wanton and pointless act of pique even by his admirers.

References for the Battle of Liegnitz:

Frederick the Great by Thomas Carlyle

Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Maria Theresa by Christopher Duffy

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Kunersdorf

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Torgau