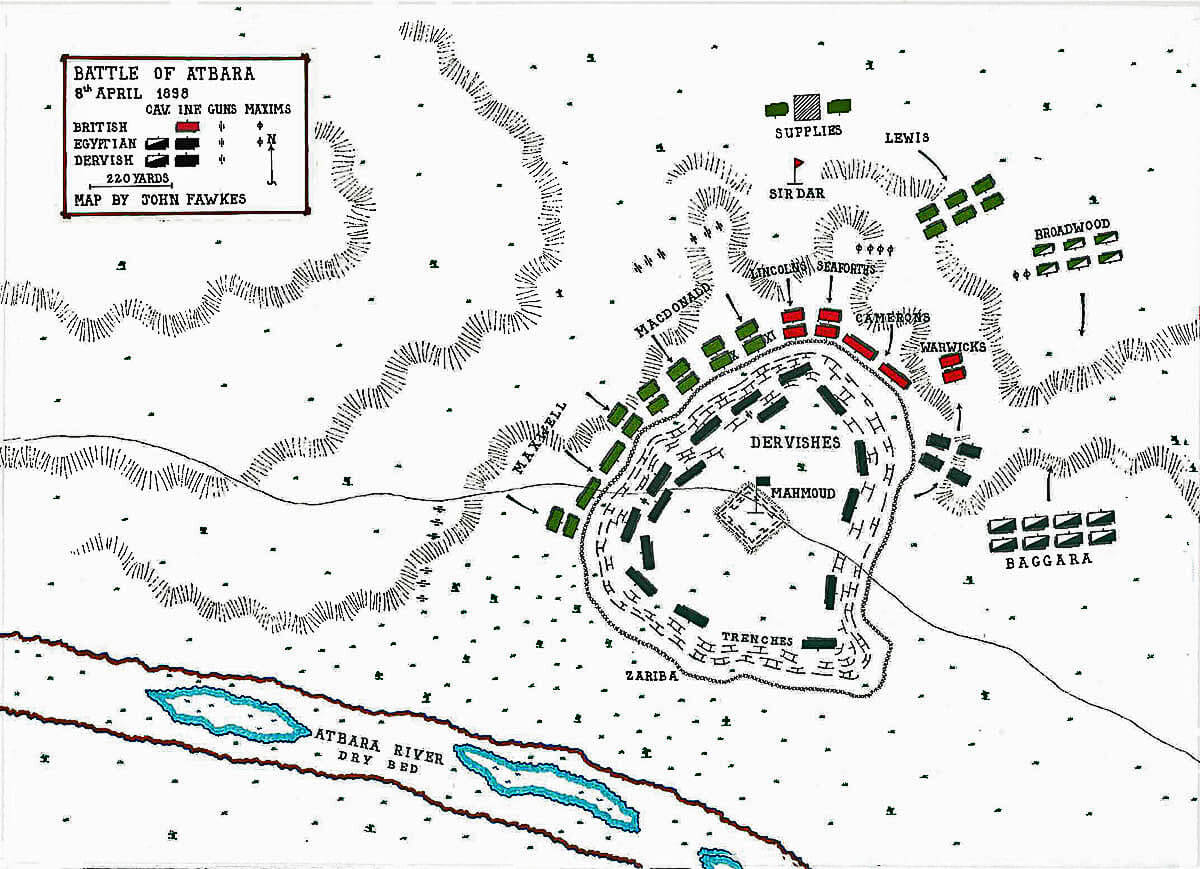

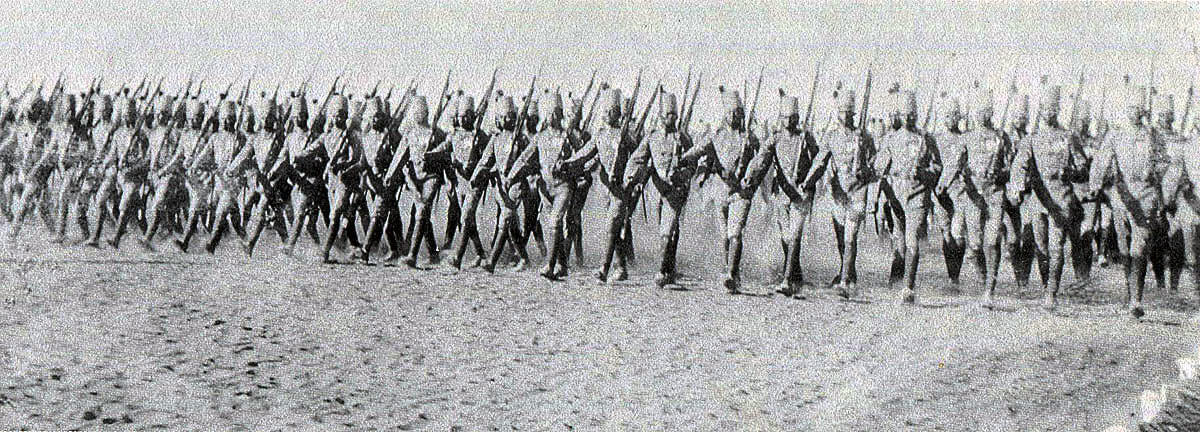

The battle in the Sudan, fought on 8th April 1898, a preliminary to Kitchener’s final advance on Khartoum and the Battle of Omdurman

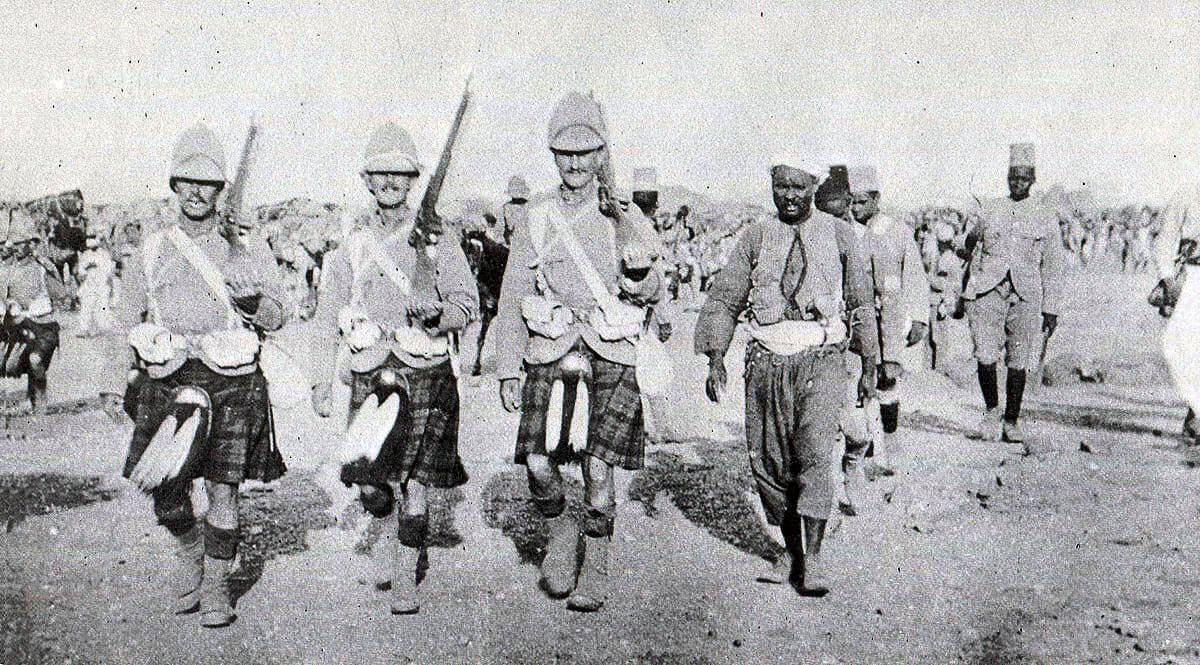

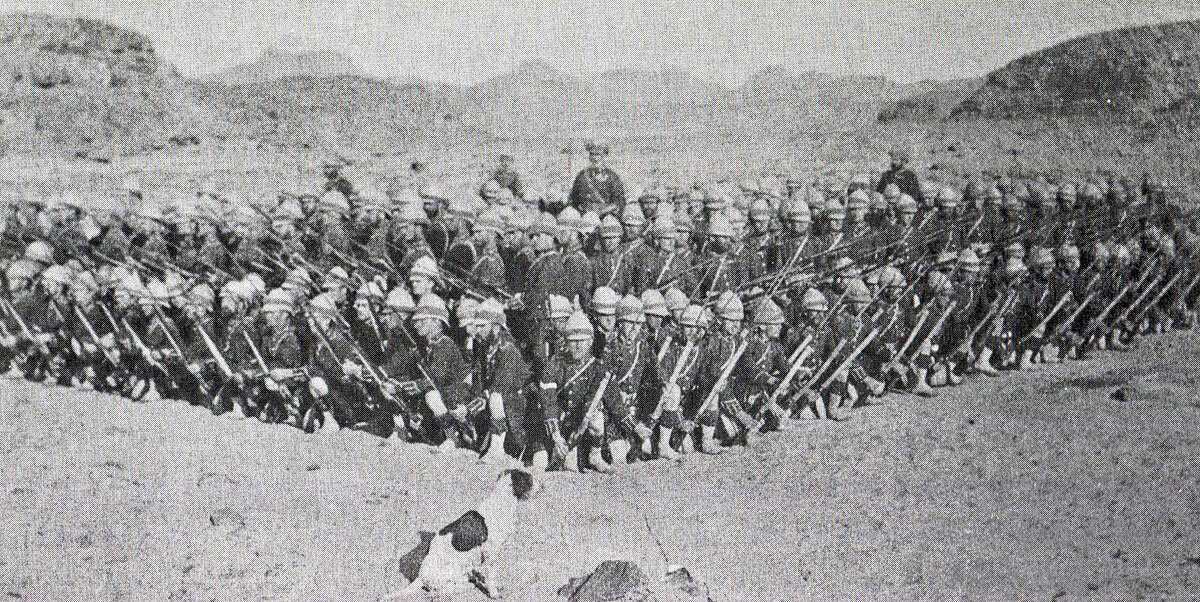

Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War: picture by Corporal John Farquharson of 1st Seaforths: 1st Seaforth Highlanders pass through the ranks of 1st Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, to storm the Dervish zeriba

The previous battle of the War in Egypt and the Sudan is the Battle of Abu Klea

The next battle of the War in Egypt and the Sudan is the Battle of Omdurman

To the War in Egypt and the Sudan index

Sirdar, Major General Sir Herbert Kitchener: Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War: print by Richard Caton Woodville

War: Conquest of the Sudan

Date of the Battle of Atbara: 8th April 1898

Place of the Battle of Atbara: On the bank of the Atbara River, near to its junction with the River Nile, in the Sudan.

Combatants at the Battle of Atbara: British and Egyptian troops against the Dervish army of the Khalif Abdullah.

Size of the Armies at the Battle of Atbara:

The Anglo-Egyptian force numbered around 10,000 troops, including 500 cavalry and some twenty-four guns. The Dervish army numbered around 15,000 men, including 5,000 Baggara mounted men.

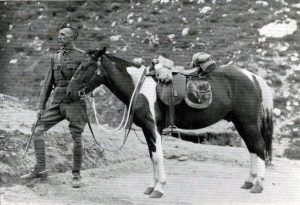

Commanders at the Battle of Atbara: The Sirdar of the Egyptian Army, Major General Herbert Kitchener, commanded the British and Egyptian troops. The Emir Mahmoud commanded the Khalif’s Dervish army.

Emir Mahmoud, the Mahdist commander, after his capture at the Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War

Winner of the Battle of Atbara: The British and Egyptian troops decisively defeated the troops of the Khalif.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Atbara:

The British troops wore the new khaki field uniforms with the characteristic pith helmet. The two Highland regiments wore the kilt. These regiments were armed with the Lee-Metford bolt action magazine rifle and bayonet. Each battalion possessed a Maxim Gun detachment of two guns, although only four of these guns were present at the Battle of Atbara.

Captain McLean’s company of 1st Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders: Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War

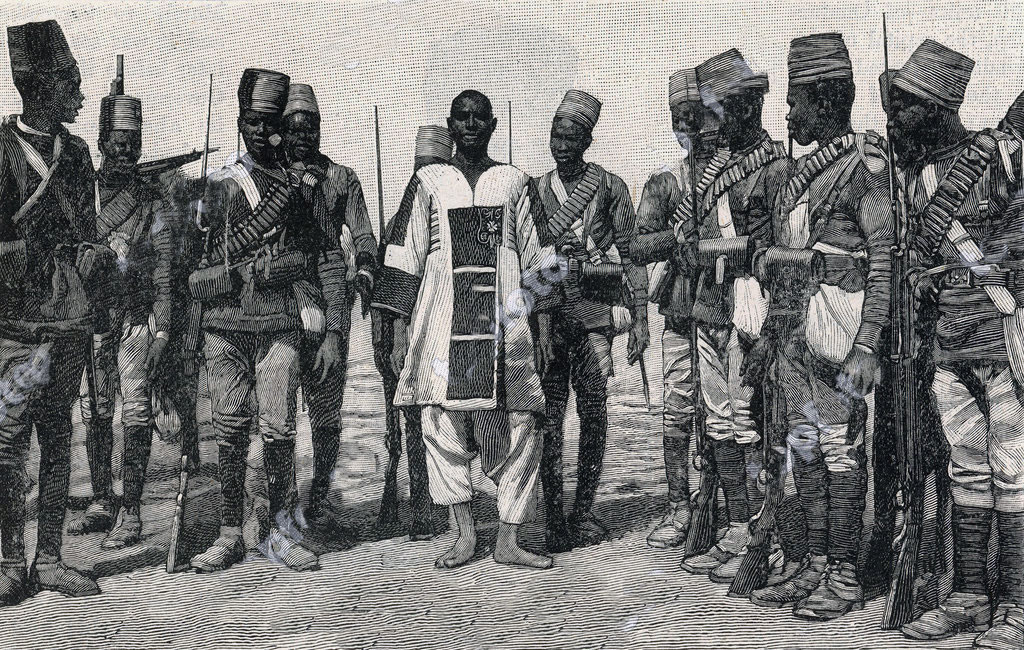

The Egyptian army was formed of Egyptian and Sudanese battalions. Many of the Sudanese were deserters or prisoners from the Dervish army. The weapon carried was the old Martini-Henry single shot lever action rifle, recently discarded by the British army, and bayonet.

These battalions were led by British officers and, after many years of training and skirmishing on the border between Egypt and the Sudan, were hardened and reliable units.

All the 500 cavalry were Egyptian, led by British officers. They also were to prove themselves effective soldiers.

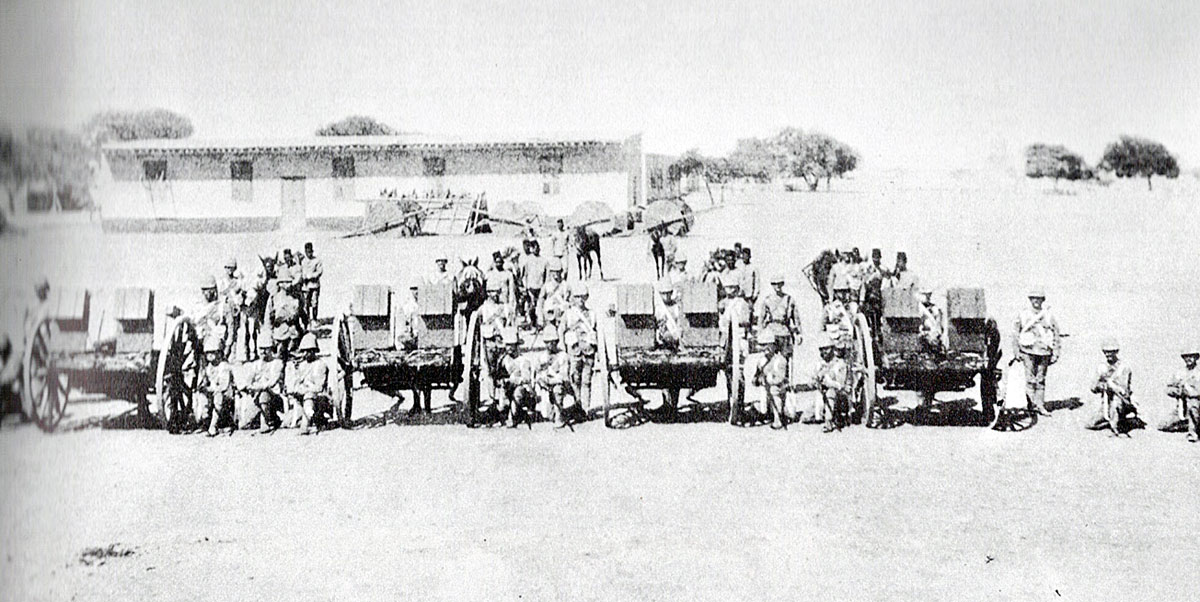

Kitchener’s army at the Battle of Atbara was accompanied by four batteries of artillery, equipped with Krupp and Maxim-Nordenfeldt guns and a rocket troop.

The Dervish army comprised Jihadi Arab and African warriors from the many tribes in the south of the Sudan, all armed with swords and spears and some with rifles taken from the Egyptian forces overwhelmed in the Mahdi’s wars in the 1880s and early 1890s, or from the Italians in Eritrea. There were some guns. 5,000 mounted Baggara tribesmen provided the cavalry arm.

Background to the Battle of Atbara:

Wolseley’s campaign in 1884/5 to rescue General Charles Gordon, besieged in Khartoum, ended unsuccessfully. Gordon died at the hands of the Mahdi’s army, before Wolseley’s troops could reach him. With Wolseley’s withdrawal into Egypt, the Dervish army of the Mahdi followed to the Egyptian border at Wadi Halfa.

The action at Ginniss prevented the Dervishes from invading Egypt. The Sudanese remained restless neighbours to the south of the Egyptian border, awaiting an opportunity to invade and drive out the Ottoman rulers.

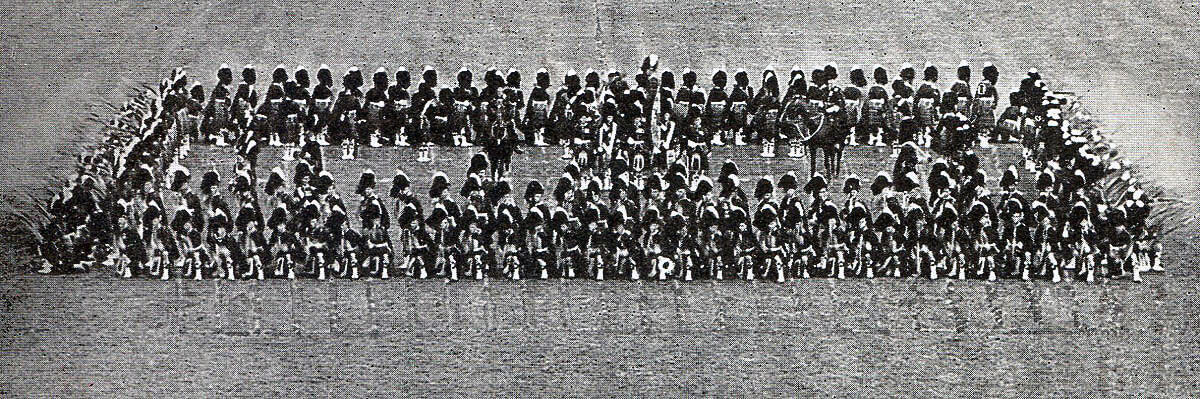

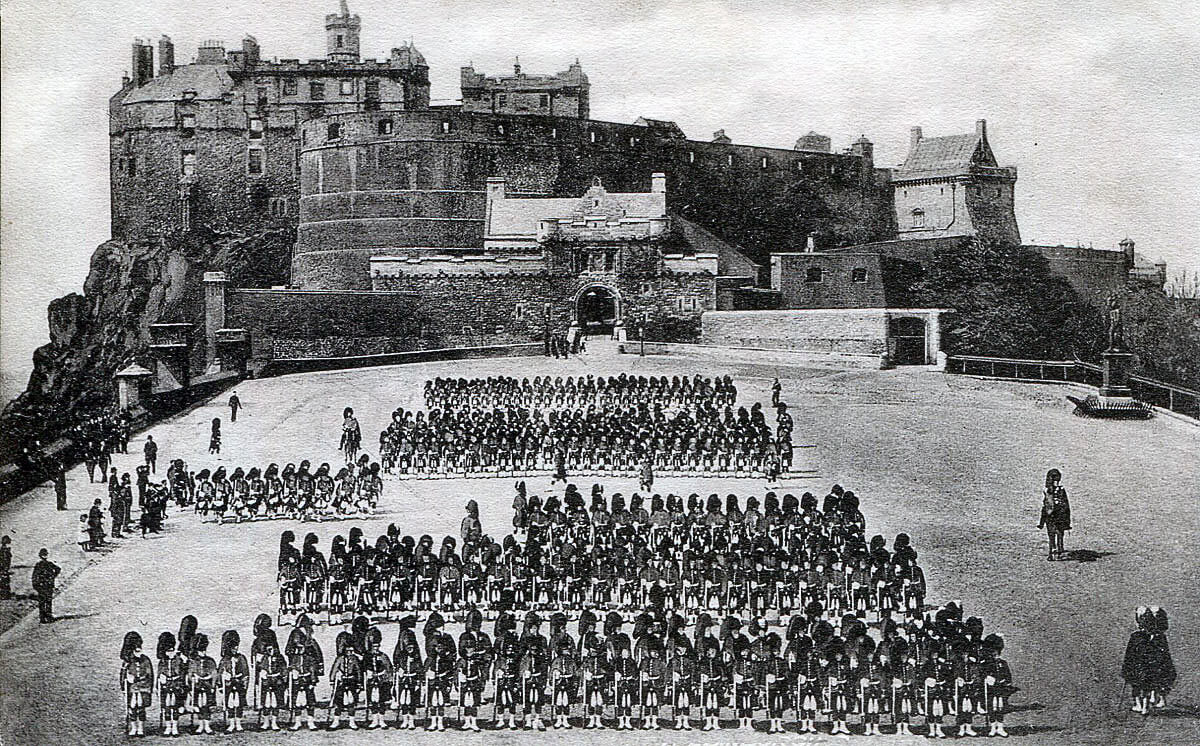

Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders on the Edinburgh Castle Esplanade: Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War

Egypt, although nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, was for all practical purposes under British rule, in the person of Britain’s Agent and Consul-General, Sir Evelyn Baring, later Lord Cromer.

The Mahdi died in June 1885, leaving the Sudan under the control of the Khalif Abdullah, the Mahdi’s appointed successor.

After the humiliating defeats of the Egyptian army in 1884 and 1885, a priority for the British administration in Egypt was to reform the Egyptian army, under a new staff of British officers and senior non-commissioned officers.

Sir Francis Grenfell was appointed Sirdar of the Egyptian army. A prominent subordinate was Colonel Horatio Herbert Kitchener.

1st Lincolnshire Regiment in Malta before leaving for the Sudan: Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War

In late 1888, in fighting around Suakin on the Red Sea coast, Grenfell heavily defeated a Sudanese force under Osman Digna.

In 1889, after the Sudanese defeat of the Abyssinians, a Dervish army under Wad-el-Nejumi advanced into Egypt, crossing the desert to the west of Wadi Halfa. Grenfell marched to intercept the invading force, with Egyptian and Sudanese troops led by British officers and, on 3rd August 1889, routed the Dervishes at Toski.

During the Toski campaign, the mounted troops were commanded by Kitchener, who subsequently returned to his duties as adjutant-general of the Egyptian army.

In 1892, Grenfell retired as Sirdar in command of the Egyptian army and Kitchener was appointed Sirdar in his place, with the British rank of major-general.

Kitchener was not an obvious or popular choice for Sirdar among the British officers of the Egyptian army, but Lord Cromer knew that Kitchener was burning to recover the lost Sudanese territory for Egypt, an ambition Cromer also held.

1st Seaforth Highlanders before leaving for Egypt: Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War

Kitchener had been much angered by the failure of the British Government to move sufficiently swiftly to rescue Gordon, a fellow officer of the Royal Engineers and under whom Kitchener had served in the Sudan. Kitchener harboured the ambition to renew the war with the Mahdists and to avenge Gordon’s death.

Several factors combined to cause the British government of Lord Salisbury to resolve to invade the Sudan, one being the heavy defeat of the Italians by the Abyssinians at Adowa in March 1896, leading to fears that the Sudanese would invade the Italian colony of Eritrea, thereby weakening the position of Italy in European circles. Within two weeks of Adowa, instructions were given to Lord Cromer to invade the Sudan.

The Egyptian advance was to be made up the River Nile. The Egyptian regiments were brought to war strength and Kitchener concentrated his army at Akasha on the Nile, the Dervishes being further up the river at Firket.

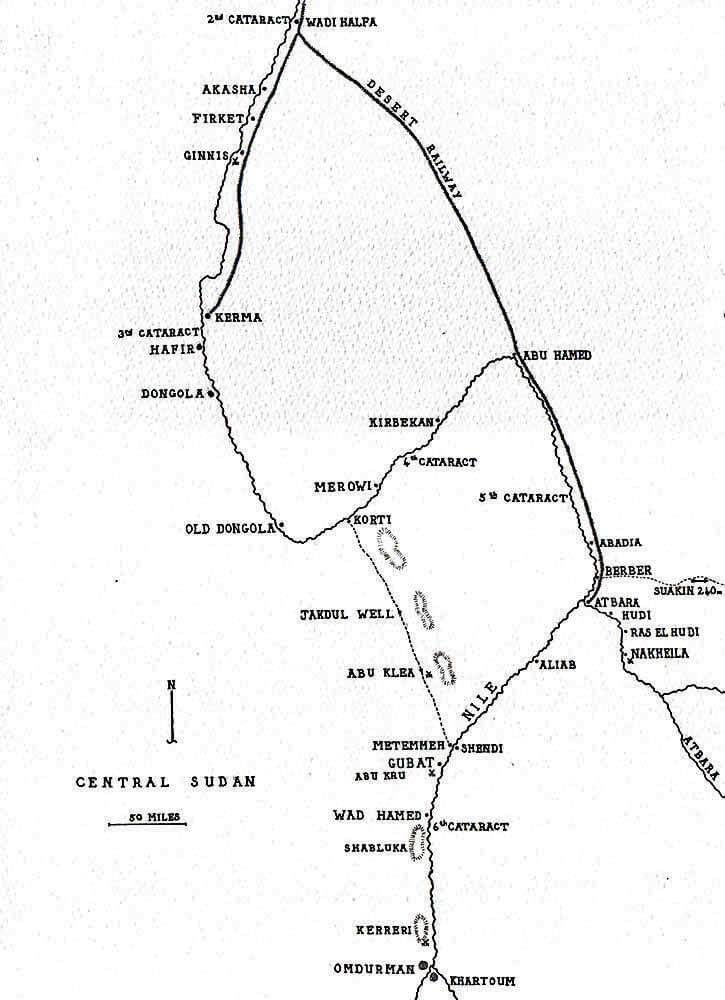

The Nile River system is central to communication through the Sudan and Egypt. The Blue Nile rises in the mountains of Abyssinia. The White Nile rises in Central Africa. These two great rivers, fed by many tributaries, meet at Khartoum and form the River Nile, winding north in two wide sweeps, before crossing the border into Egypt and flowing through that country to the Mediterranean.

The section of the River Nile between Wadi Halfa, on the Egyptian border and Khartoum, the target for Kitchener’s invasion, was in places wide and navigable. But it also contained the series of cataracts, numbered 3rd to 6th, where the river drops significantly in height and changes to rapids. For large vessels, such as the river steamers to be relied upon by Kitchener for supply and fire support, these cataracts were only navigable in the wet season, when the Nile was filled with flood water from the southern mountains. Even then, navigating the cataracts could be hazardous. The steamer El Teb capsized while trying to fight its way up the 4th Cataract.

At the height of the dry season, which ran from January to June, the cataracts became impassable to the river steamers, trapping them in whichever section of the river they happened to be when the water level dropped.

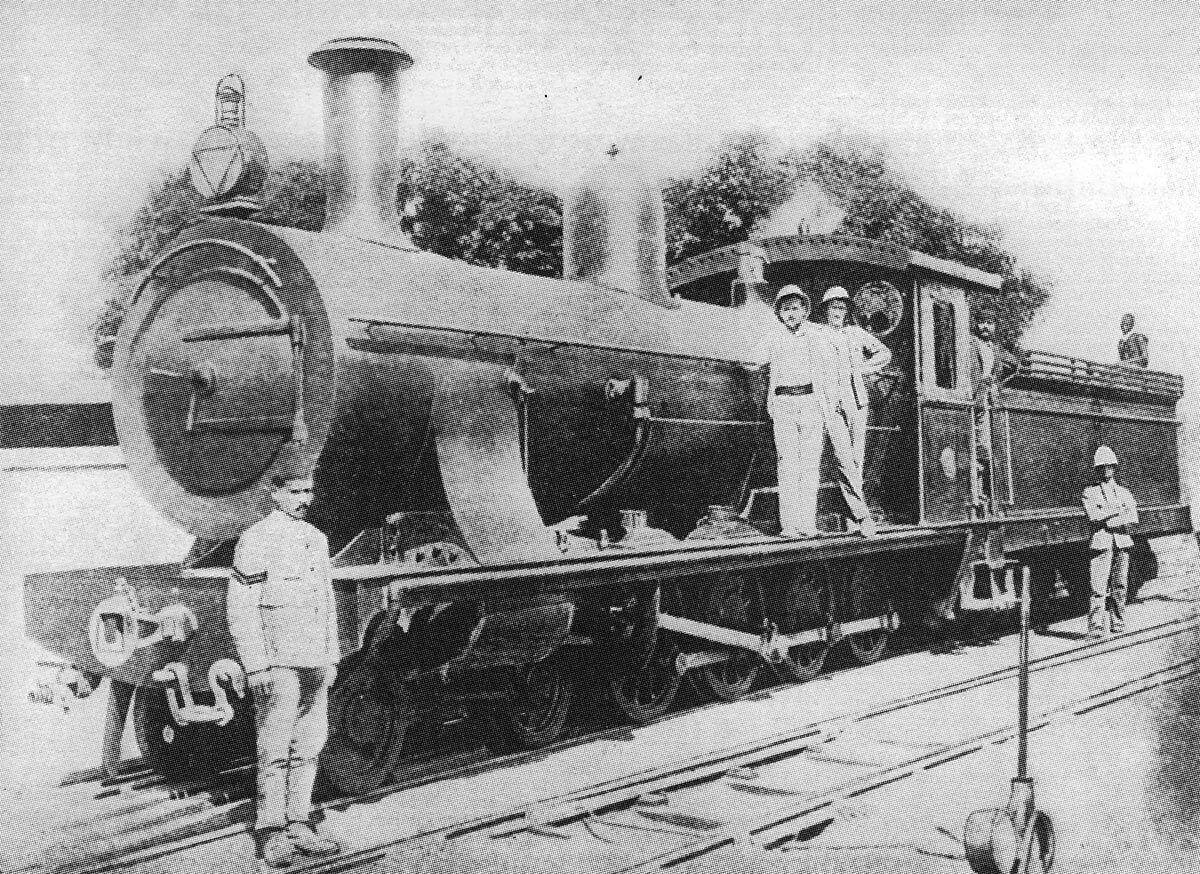

As Kitchener’s force advanced up the River Nile, the desert railway was extended to provide much of the transport necessary to convey men and supplies from Egypt (the new steamers were built in England and transported from Egypt on the desert railway). Ending at Wadi Halfa, in the first months of the war the railway was extended along the River Nile to Kerma, at the 3rd Cataract.

Account of the Battle of Atbara:

On 7th June 1896, Kitchener captured Firket, further up the River Nile, after a night march. He felt able to write to Lord Cromer and inform him that the Egyptian and Sudanese troops of the Egyptian army, under their British officers, could be considered fully reliable.

After delays caused by disease and adverse weather, which severely damaged the railway line, on 5th September 1896, Kitchener moved out to begin the assault on the Dervish positions at Dongola, situated on the first major loop in the River Nile.

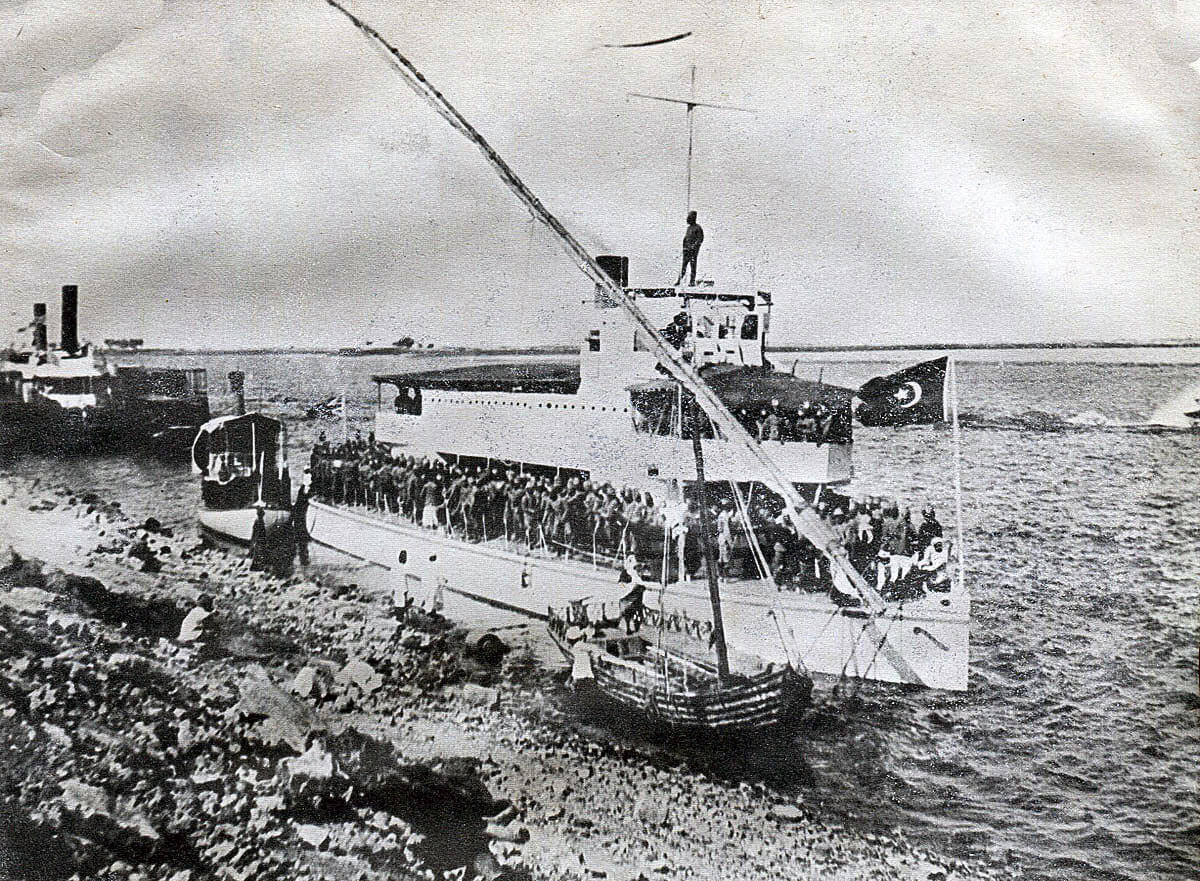

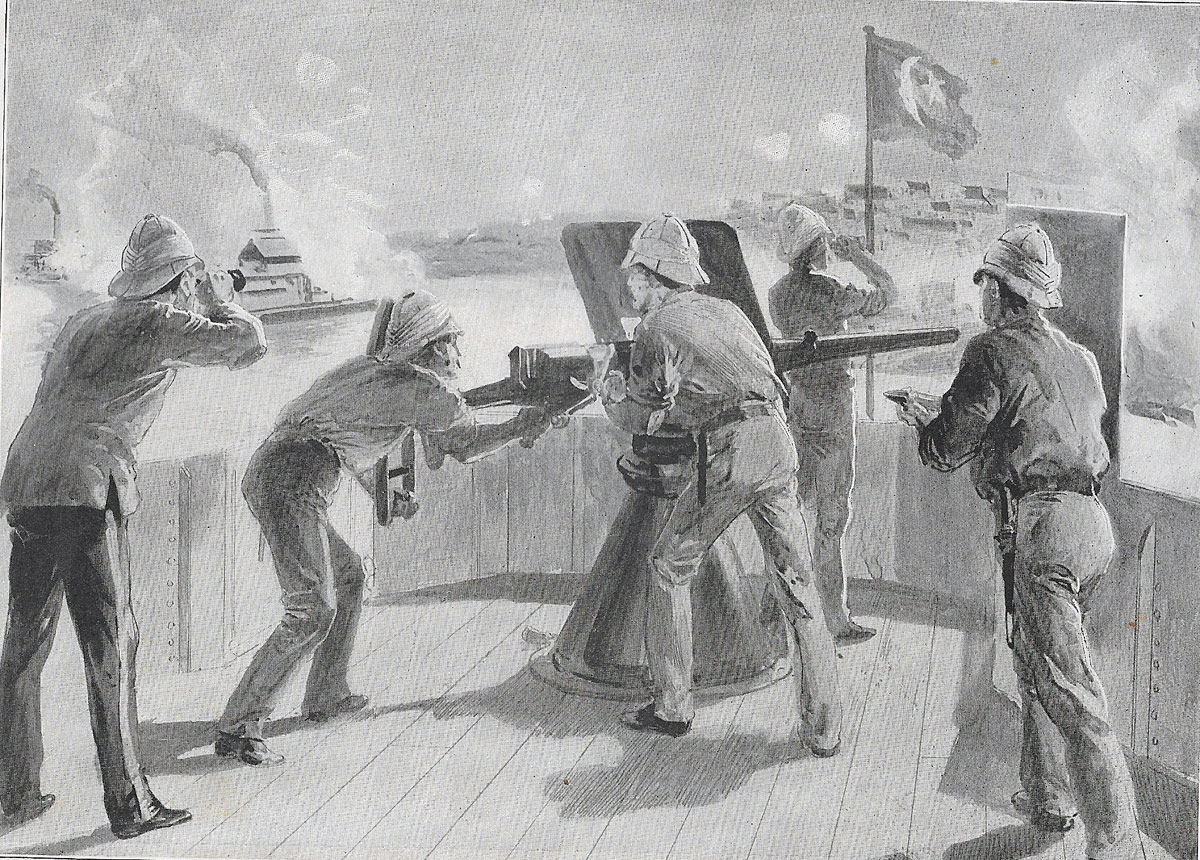

Kitchener was equipped with a number of river steamers, to bring supplies and men up the River Nile and to attack the Dervish positions along the river. In addition to the old and ill-equipped vessels from the previous war, Kitchener was supported by his new gunboat, the Zafir, built in Britain and recently launched on the River Nile. As the Zafir moved into the fairway, its boiler burst, leaving it helpless until a new boiler could be brought up from the railhead and installed.

Kitchener pushed on to Dongola, manoeuvring the Dervishes out of their positions at Hafir, with the support of the older vessels.

In the face of Kitchener’s powerful force, the Dervish commander, Wad Bishara abandoned Dongola, which Kitchener occupied on 23rd September 1896.

There was then a hiatus in the campaign. The Egyptian government was unable to fund a further advance, despite the evident need to take advantage of the successes achieved and in the light of threatened changes in the international situation.

The French were making overtures to the Abyssinians, with a view to extending their influence across Equatorial Africa and the Khalif was seeking to persuade the Abyssinians to join him in resisting the Egyptian invasion of the Sudan.

Cromer dispatched Kitchener to London, to obtain the necessary support from the British government. Kitchener achieved this, being promised additional finance and the commitment of British troops to his force.

‘Dongola’ class engine of the Sudanese Desert Railway in 1898: Battle of Abu Klea on 17th January 1885 in the Sudanese War

The Desert Railway:

A key feature of Kitchener’s plan for the next stage of the campaign was to build a railway across the two hundred and twenty-five miles of the Nubian Desert, from Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamed, thereby circumventing the long difficult curve of the Nile through Dongola and significantly shortening his supply line.

All the advice given to Kitchener was that this railway project was too difficult. Kitchener ignored the advice and proved himself to be right.

The work of building the Desert Railway began on 1st January 1897, under the supervision of junior officers from the Royal Engineers, commanded by a Canadian officer, Lieutenant Percy Girouard.

By 23rd July 1897, one hundred and three miles of track was complete. The difficulty now was that the railway was approaching Abu Hamed on the River Nile, still held by the Khalif’s forces.

Kitchener ordered General Hunter to march from Merowi, on the Nile bulge, to Abu Hamed and capture the town.

‘Lament in the Desert’: Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders burying their casualties: Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War: picture by Lady Butler

The main formation in Hunter’s force for this task was the Sudanese brigade commanded by Colonel Hector McDonald, commissioned from the 91st Highlanders for his conduct in the Second Afghan War.

Hunter marched one hundred and fifty miles from Merowi to Abu Hamed, arriving on 7th August 1897 and drove the Dervish forces out of the town, largely annihilating them. He was just in time. The Dervish fugitives from Abu Hamed met the relief force marching to their rescue, a short distance from the town.

Kitchener’s Nile flotilla, comprising the old gun boats and the three newly built boats, followed Hunter up to Abu Hamed.

The next major Dervish garrison on the River Nile was at Berber, one hundred and twenty miles south of Abu Hamed. The Dervish Emir holding Berber, feeling that he was not properly supported, abandoned Berber and withdrew to the confluence of the Nile with the Atbara River.

The campaign authorised by the British Government permitted Kitchener to advance to Abu Hamed, where he was required to stop. The opportunity now arose to take Berber without fighting for it. The town was an important link between Khartoum and Suakin on the Red Sea coast. It was also a significant step on the road to Khartoum. On the other hand, with the coming of the dry season, Kitchener’s force and its steamers might well be stuck in Berber by the falling water level in the Nile, at a place significantly nearer to the Khalif’s main army in Omdurman.

Cromer agreed that Kitchener should advance and take Berber, but that he should go no further.

Concerns were growing, for Cromer and the Home Government, that Kitchener was becoming difficult to control, with his clear determination to advance to Khartoum, defeat the Dervish armies of the Khalif and conquer the Sudan at the first opportunity.

Cameron Highlanders with Egyptian and Sudanese troops: Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War

However, Kitchener recognised that the final phase of the conquest of the Sudan required British troops and could not be carried out with just the Egyptian and Sudanese regiments of the Egyptian army he currently commanded.

The Advance to the Atbara River:

In January 1898, British troops began to arrive in the Sudan from the garrison in Egypt; 1st Royal Warwickshire Regiment, 1st Seaforth Highlanders and 1st Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders and from Malta, 1st Lincolnshire Regiment. These battalions were brigaded under Major-General Gatacre.

Kitchener concentrated his force of British, Egyptian and Sudanese troops at Berber, sending a Sudanese brigade further up the River Nile to the mouth of the Atbara River to build a fort.

The Khalif’s general, the Emir Mahmoud, commanding the force of Dervishes holding Metemmeh, around one hundred miles up the River Nile from Berber, on the west bank, was keen to lead his forces into action against the invading Egyptian army. The Khalif finally agreed that Mahmoud should move down the river and attack Kitchener’s troops at Berber.

Mahmoud crossed to the east bank of the River Nile, where he joined the army of Osman Digna, from the eastern Sudan. Despite his apparent enthusiasm for action, it took Mahmoud a couple of weeks to cross the River Nile, under the observation of Kitchener’s riverboats.

Mahmoud and Osman Digna finally began their advance north on 13th March 1898, marching along the east bank of the River Nile, watched by Kitchener’s steamers.

Cameron Highlanders forming square in the desert: Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War

To meet the threat, Kitchener moved his army up the river, to concentrate behind Atbara Fort.

On 15th March 1898, Mahmoud changed the direction of his march to the east-north-east, away from the River Nile and towards the Atbara River, upstream of the Nile junction. His intention now was to cross the Atbara River and circle around behind Atbara, to attack Berber from the eastern desert. He no longer entertained the prospect of a head-on clash with Kitchener.

In response to this move, Kitchener marched his army north, up the Atbara River, to intercept Mahmoud’s force, arriving at Hudi on 20th March 1898.

1st Lincolns resting during the advance to the Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War

Apparently in response to Kitchener’s move, Mahmoud’s force again changed direction, this time to an easterly route, to cross the Atbara River even further upstream. The next day, Kitchener arrived at Ras-El-Hudi, some fifteen miles north of the point where the Dervishes were crossing to the east bank of the Atbara River.

At this time of year, the Atbara River did not contain a consistent flow of water and could be crossed on foot.

Mahmoud’s plans were in disarray. He was now too far south for his army to march through the desert to attack Berber, his water carrying capacity being inadequate, even for a force of desert dwellers equipped with camels.

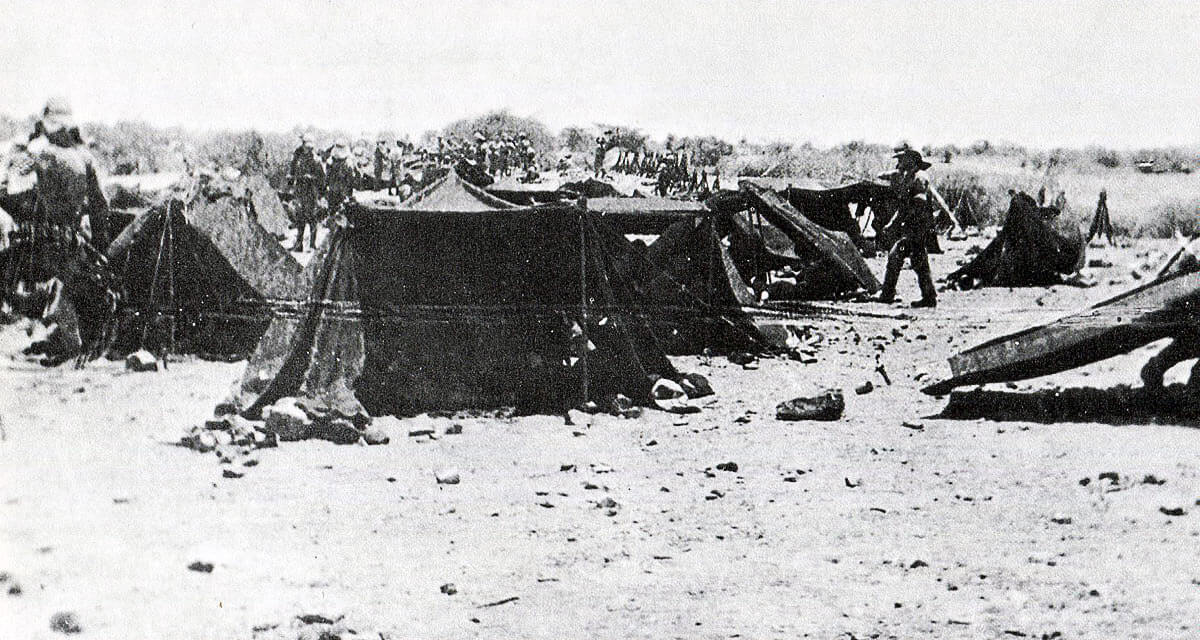

As it was clear to Mahmoud that he was likely to be attacked, he ordered his Dervishes to build a zeriba of thorn fences, trenches and rifle pits on the east bank of the river, where he awaited the arrival of the Anglo-Egyptian army.

Kitchener’s infantry waited in their make-shift camp at Ras-El-Hudi, while the cavalry under Colonel Broadwood scouted along the Atbara River to find Mahmoud’s force.

British brigade advancing at the Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War: sketch by Melton Prior

On 30th March 1898, Broadwood’s cavalry discovered the zeriba at Nakheila.

Kitchener was in the meantime finding it difficult to decide whether to attack Mahmoud, or to stay in his position on the Atbara River and await a movement by the Dervishes. Gatacre urged an attack, but Hunter, commanding the Egyptians and Sudanese, advised caution. Finally, Hunter changed his mind and Kitchener resolved to attack the Dervish zeriba.

On 4th April 1898, Kitchener’s army moved a further four miles towards Nakheila.

A cavalry reconnaissance approached the zeriba and formed the view that it was deserted. Suddenly fire was opened from the thorn walls and trenches and the Baggara horse launched an attack on the Egyptian cavalry force.

The Egyptians conducted a spirited rear-guard action, as they withdrew to the camp.

At sunset on 7th April 1898, the British, Egyptian and Sudanese troops of Kitchener’s army marched out of camp, heading south towards the zeriba, the four infantry brigades each in a square, with the four British battalions leading. At around 4am the force halted on a plateau twelve hundred yards from the zeriba.

At dawn on 8th April 1898, the army prepared for the assault on the zeriba, the brigades forming with the British on the left, MacDonald’s brigade of three Sudanese and one Egyptian battalion in the centre, and Maxwell’s Sudanese brigade on the right. The flank brigades each deployed a battalion in line, with the remaining three battalions following in column. The Cameron Highlanders formed the forward line of the British brigade.

In the rear, on the left, Lewis’s brigade guarded the supply camels. The Camel Corps formed a reserve in the centre.

Along the line were deployed the 24 guns, the 4 maxims and the rocket detachment.

The Egyptian cavalry, under Broadwood, guarded the open left flank beyond the British brigade.

To the front of the attacking brigades was the line that marked the thorn fence of the zeriba. A war correspondent reported that there was a haze of dust above the zeriba, as if rifle pits and trenches were still being dug.

Cameron Highlanders officer and an officer of an Egyptian Regiment in the desert: Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War

At 6.20am, Kitchener’s four artillery batteries opened fire, methodically bombarding every part of the Dervish camp.

A force of Baggara horsemen moved out of the rear of the zeriba and made to attack the left flank of the army, but was driven back by fire from two of the maxims, supported by Broadwood’s cavalry.

After a bombardment lasting some seventy-five minutes, the artillery ceased firing and the infantry began to advance on the zeriba, halting to fire volleys into the Dervish positions.

At about three hundred yards distance, the Dervish riflemen opened a return fire on the advancing infantry.

Seaforth Highlanders storming the Dervish zeriba at the Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War: print by Richard Caton Woodville

With rising casualties, Kitchener’s battalions reached the zeriba. The Camerons, the front-line battalion of the British brigade, fired into the camp, while the Seaforths pulled the thorn hedge aside and rushed through into the positions behind. The battalions along the line stormed through the zeriba and engaged the Dervishes, as they emerged from their trenches and rifle pits.

The 11th Sudanese suffered particularly heavy casualties, their position, as they pressed through the thorn hedge, putting them opposite Mahmoud’s redoubt. Mahmoud’s personal bodyguard opened a devastating fire that annihilated a company of the 11th, before the 10th and 11th Sudanese stormed the redoubt, wiping out the defenders and capturing Mahmoud.

Cameron Highlanders storming the Zeriba at the Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War: print by Stanley Berkeley

Some of the Dervishes broke out of the camp on the desert side to the east and attempted to charge around the flank of the British first line. These attackers were caught by the fire of the Warwicks, in the second line of the British brigade.

Kitchener’s troops fought through the camp to the Atbara River, where they found the Dervishes escaping across the dried river bed to the west bank and opened fire on them.

The Baggara horse escaped south, along the Atbara River, with Osman Digna, the commander of the eastern Dervish forces.

At 8.30am the battle was over and the bugles sounded the ‘Cease Fire’.

Emir Mahmud brought prisoner to General Kitchener, after the Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War

Mahmoud, rescued by British officers from the Sudanese soldiers who had captured him, was brought before Kitchener.

After ransacking the Dervish camp, Kitchener’s army formed up and marched back to their positions at Atbara Fort and Berber.

Casualties at the Battle of Atbara:

In excess of 2,000 Dervish dead were found inside the zeriba. A large number of Dervishes were captured, most of whom were enlisted in Kitchener’s Sudanese battalions.

Seaforth and Cameron Highlanders burying their dead after the Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War

Total losses in Kitchener’s army were 80 killed and 479 wounded. The leading British battalion, 1st Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders suffered 44 casualties, including 3 officers killed and 1 wounded. The Seaforths suffered 22 casualties, including 6 officers killed and wounded. 1st Royal Warwicks suffered 11 casualties and 1st Lincolns 13 casualties.

Among the non-British troops, the Sudanese battalions suffered 375 casualties, while the Egyptian battalions suffered 14 casualties.

Battle Honour and Campaign Medal for the Battle of Atbara:

The Battle Honour of ‘Atbara’ was awarded to the four British infantry regiments present.

The campaign medals awarded were the Queen’s Sudan Medal 1896-1898 and the Khedive’s Sudan Medal 1896-1908, with the clasp on the Khedive’s medal of ‘The Atbara’.

Follow-up to the Battle of Atbara:

Follow-up to the Battle of Atbara:

Immediately after the battle, an attempt was made at pursuit into the desert on the west bank of the Atbara by Colonel Lewis’s brigade, but the ground was too difficult and the escaping Dervishes too widely dispersed. Lewis abandoned the attempt and withdrew to the main army.

After the return to Berber, Kitchener awaited the reinforcements of British troops considered necessary to complete the defeat of the Khalif and the capture of Khartoum, the capital of the Sudan.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Atbara:

- Before his appointment to the command of the British brigade in the Sudan, Major General Gatacre made a name for himself commanding a brigade in the relief of Chitral, on the North-West Frontier of India in 1895. Gatacre was known to his troops as ‘Backacher’, due to his demands upon them. Gatacre commanded a division at the unsuccessful Battle of Stormberg, in the South African War in 1899. This ended his active military career.

- Almost all the prisoners taken at Atbara were African Sudanese, as the Arabs mostly fought to the last. These prisoners readily joined the Sudanese battalions and many later fought at Omdurman against the Khalif’s forces.

- ‘Sergeant Whatsisname’: Rudyard Kipling’s poem in praise of the British non-commissioned officers who doggedly trained the Egyptian and Sudanese battalions of the Khedive’s Egyptian army, that so distinguished themselves in Kitchener’s campaign to re-conquer the Sudan. (in fact the poem is ‘Sergeant Whatisname’, but is changed to adapt to more modern English usage with the addition of an ‘s’).

Said England unto Pharaoh, “I must make a man of you,

That will stand upon his feet and play the game;

That will Maxim his oppressor as a Christian ought to do,”

And she sent old Pharaoh Sergeant Whatsisname.

It was not a Duke nor Earl, nor yet a Viscount —

It was not a big brass General that came;

But a man in khaki kit who could handle men a bit,

With his bedding labelled Sergeant Whatsisname.

Maxim gun detachment of 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers attached to the British brigade: Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War

Said England unto Pharaoh, “Though at present singing small,

You shall hum a proper tune before it ends,”

And she introduced old Pharaoh to the Sergeant once for all,

And left ’em in the desert making friends.

It was not a Crystal Palace nor Cathedral;

It was not a public-house of common fame;

But a piece of red-hot sand, with a palm on either hand,

And a little hut for Sergeant Whatsisname.

Said England unto Pharaoh, “You ‘ve had miracles before,

When Aaron struck your rivers into blood;

But if you watch the Sergeant he can show you something more. ‘

He’s a charm for making riflemen from mud.”

It was neither Hindustani, French, nor Coptics;

It was odds and ends and leavings of the same,

Translated by a stick (which is really half the trick),

And Pharaoh harked to Sergeant Whatsisname.

(There were y ears that no one talked of; there were times of horrid doubt —

There was faith and hope and whacking and despair —

While the Sergeant gave the Cautions and he combed old Pharaoh out,

And England didn’t seem to know nor care.

That is England’s awful way o’ doing business —

She would serve her God (or Gordon) just the same —

For she thinks her Empire still is the Strand and Holborn Hill,

And she didn’t think of Sergeant Whatsisname.)

Rudyard Kipling, author of ‘Sergeant Whatsisname’: Battle of Atbara on 8th April 1898 in the Sudanese War

Said England to the Sergeant, “You can let my people go!”

(England used ’em cheap and nasty from the start),

And they entered ’em in battle on a most astonished foe —

But the Sergeant he had hardened Pharaoh’s heart

Which was broke, along of all the plagues of Egypt,

Three thousand years before the Sergeant came

And he mended it again in a little more than ten,

Till Pharaoh fought like Sergeant Whatsisname.

It was wicked bad campaigning (cheap and nasty from the first),

There was heat and dust and coolie-work and sun,

There were vipers; flies, and sandstorms, there was cholera and thirst,

But Pharaoh done the best he ever done.

Down the desert, down the railway, down the river,

Like Israelites From bondage so he came,

‘Tween the clouds o’ dust and fire to the land of his desire,

And his Moses, it was Sergeant Whatsisname!

We are eating dirt in handfuls for to save our daily bread,

Which we have to buy from those that hate us most,

And we must not raise the money where the Sergeant raised the dead,

And it’s wrong and bad and dangerous to boast.

But he did it on the cheap and on the quiet,

And he’s not allowed to forward any claim —

Though he drilled a black man white, though he made a mummy fight,

He will still continue Sergeant Whatsisname —

Private, Corporal, Colour-Sergeant, and Instructor —

But the everlasting miracle’s the same!

References for the Battle of Atbara:

The River War by Winston Churchill must be considered the major reference

War on the Nile by Michael Barthorp

British Battles on Land and Sea by Grant

The previous battle of the War in Egypt and the Sudan is the Battle of Abu Klea

The next battle of the War in Egypt and the Sudan is the Battle of Omdurman

To the War in Egypt and the Sudan index