Cornwallis’s Pyrrhic victory over Nathaniel Green in the North Carolina countryside on 15th March 1781

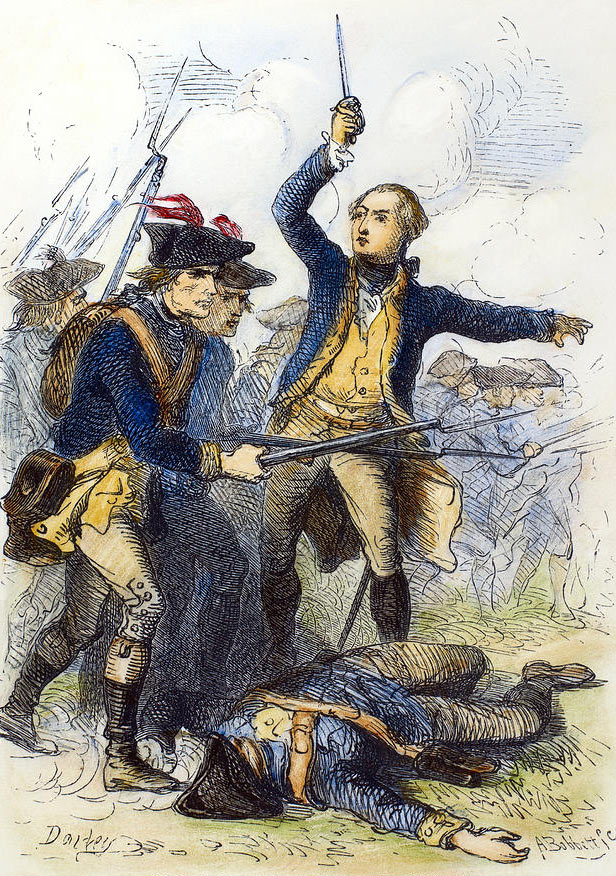

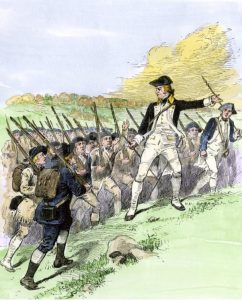

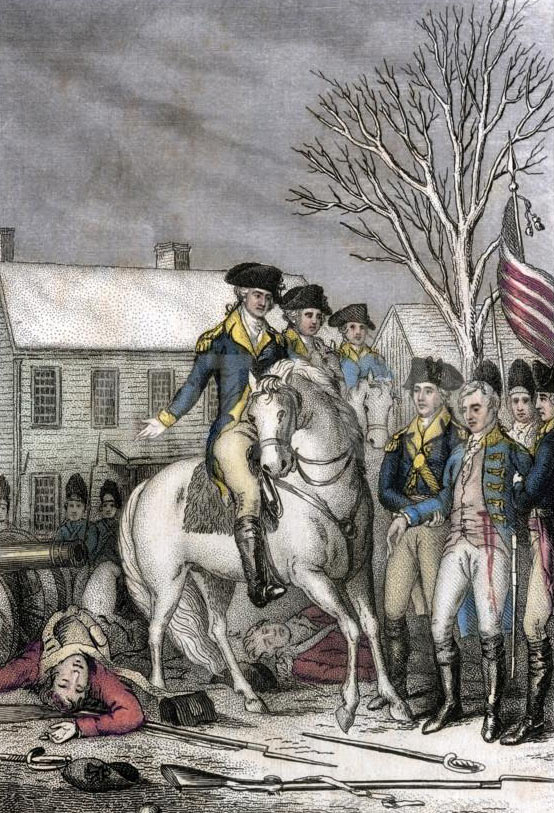

1st Maryland Regiment at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on 15th March 1781 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Frederick Coffay Yohn

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Cowpens

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Yorktown

To the American Revolutionary War index

Battle: Guilford Courthouse

War: American Revolutionary War

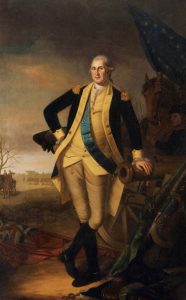

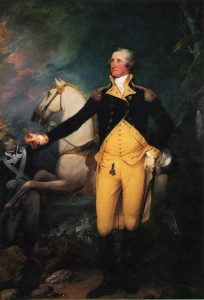

Major-General Nathaniel Greene: Battle of Guilford Courthouse on 15th March 1781 in the American Revolutionary War

Date of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse: 15th March 1781

Place of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse: North Carolina in the United States of America.

Combatants at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse: British against the Americans.

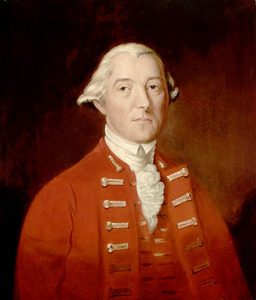

Generals at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse: Major-General Lord Cornwallis against Major-General Nathaniel Greene.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse: Around 1,900 British troops against 4,400 Americans troops.

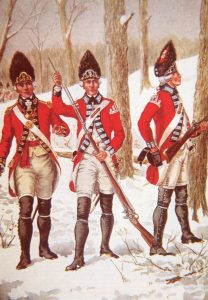

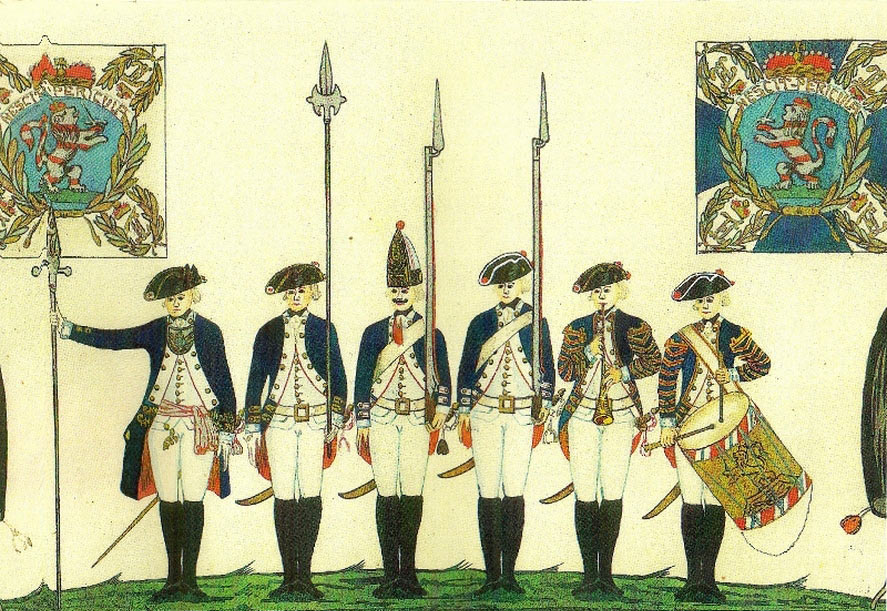

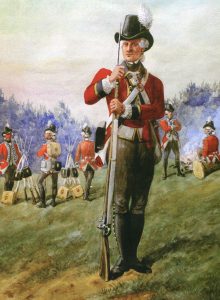

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse: The British infantry wore red coats, with bearskin caps for grenadiers, tricorne hats for battalion companies and caps for the light infantry. The Highland Scots troops wore the kilt and feather bonnet.

Major-General Lord Cornwallis: Battle of Guilford Courthouse on 15th March 1781 in the American Revolutionary War

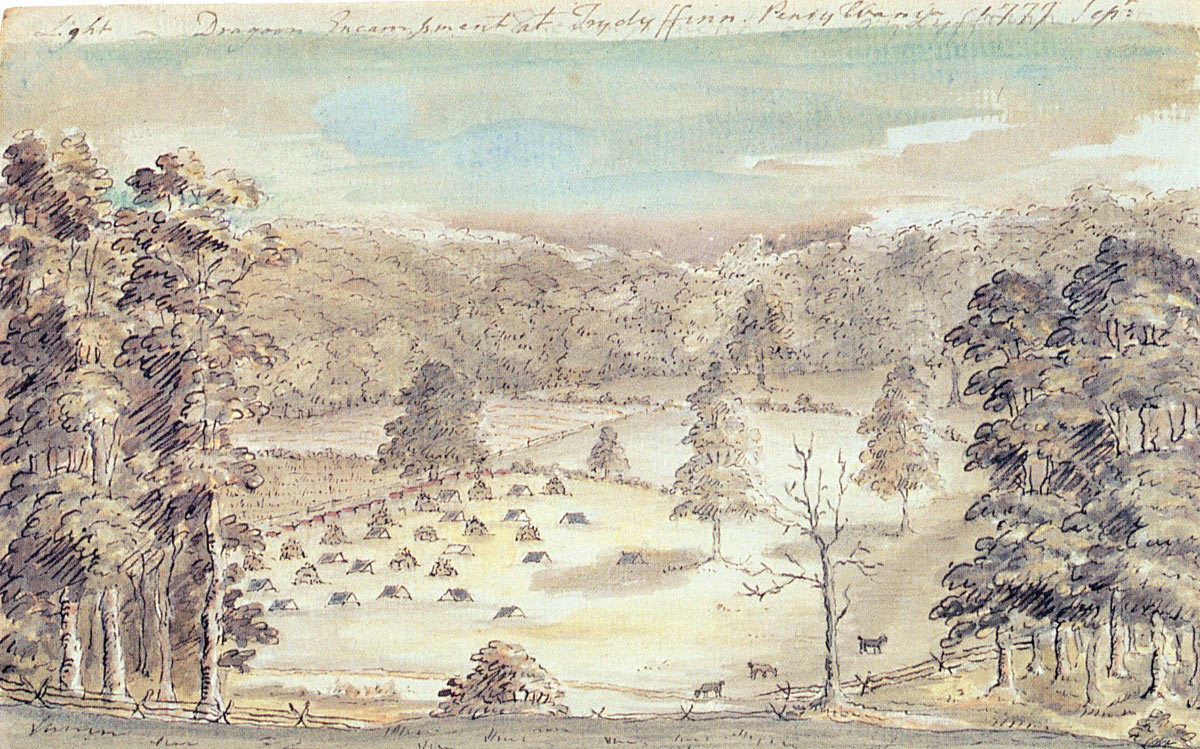

The two regiments of British light dragoons serving in America, the 16th and 17th, arrived in America wearing red coats and crested leather helmets. As the war progressed, the light dragoons abandoned their red coats for green.

Tarleton’s legion wore a uniform of green. The mounted men wore light dragoon helmets.

The American troops dressed as best they could. Increasingly, as the war progressed, infantry regiments of the Continental Army took to wearing mostly blue or brown uniform coats. The American militia continued in rough clothing.

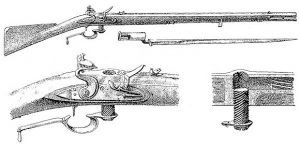

The infantry of both sides were armed with muskets. The British and German infantry carried bayonets. The Highland Scots troops carried broadswords as an additional weapon.

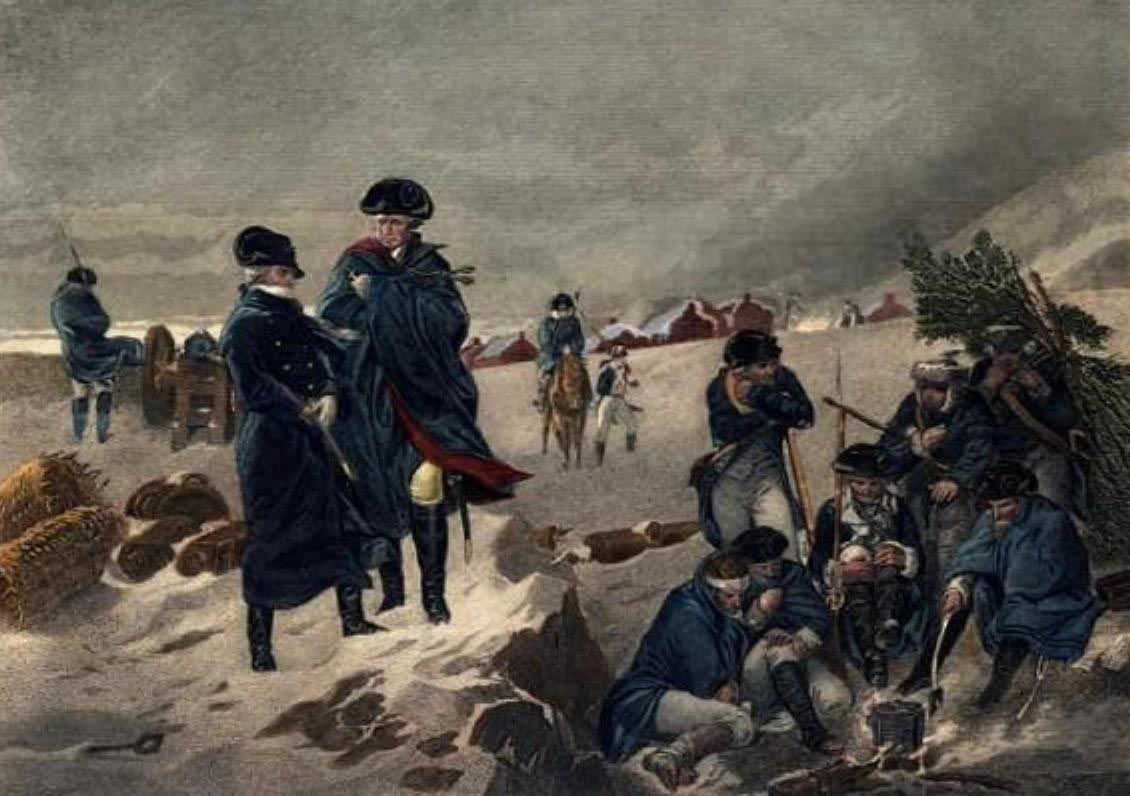

During the winter of 1777/8 in Valley Forge, Steuben insisted that the American Continental troops be issued with bayonets, whose use Steuben’s training dealt with, so that they could meet the British and German infantry on an equal footing in hand to hand fighting. This took time to implement in full.

Grenadiers of the Coldstream Guards: Battle of Guilford Courthouse on 15th March 1781 in the American Revolutionary War

Many men in the Pennsylvania and Virginia militia regiments carried rifled weapons, as did other backwoodsmen. Washington and Steuben were against the use of rifles, as they took longer to load than a smooth bore musket. In battles such as Cowpens, the accuracy of the American rifles over a long range was an important asset.

Winner of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse: The British won a Pyrrhic victory.

British Regiments at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse:

1 troop of the 17th Light Dragoons (incorporated in Tarleton’s Legion), 2 composite battalions of Foot Guards (comprising men from the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Foot Guards), 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, 33rd Foot, 71st Fraser’s Highlanders (disbanded at the end of the war), Bose’s Hessian Regiment, Light Infantry, Royal Artillery and Tarleton’s Light Dragoons.

American Regiments at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse:

1st and 5th Maryland Regiments, Delaware Infantry, 4th and 5th Virginia Regiments, Lee’s Legion, Light Infantry, North Carolina Militia, Virginia Militia, Lieutenant-Colonel William Washington’s Light Dragoons and 2 companies of artillery with 4 six pounder guns.

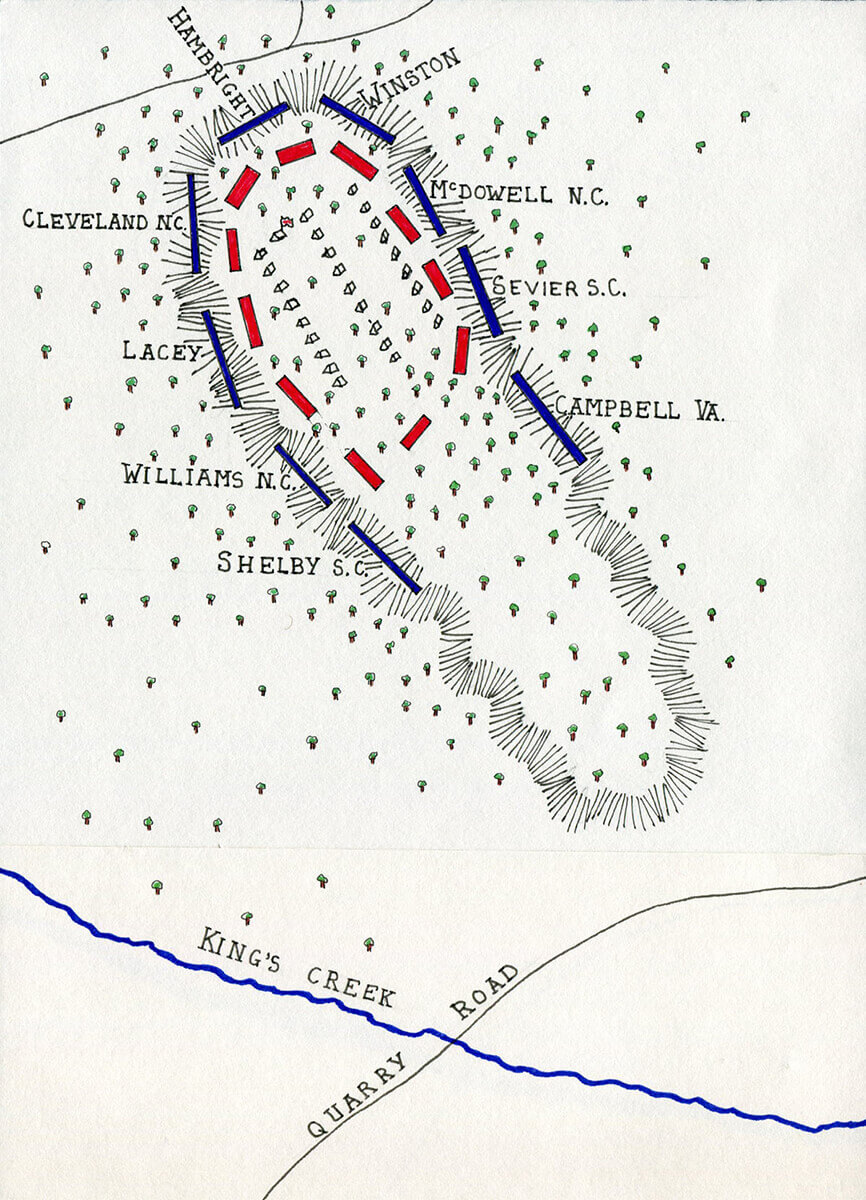

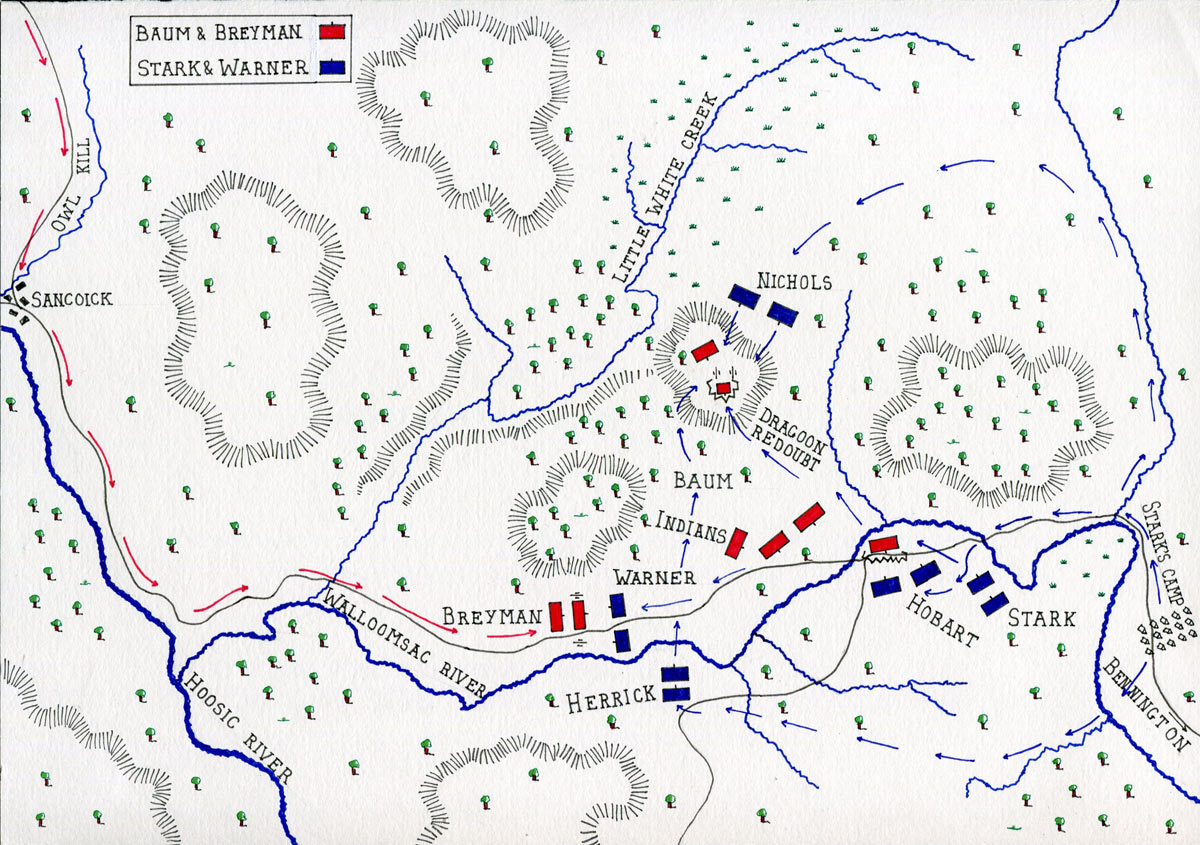

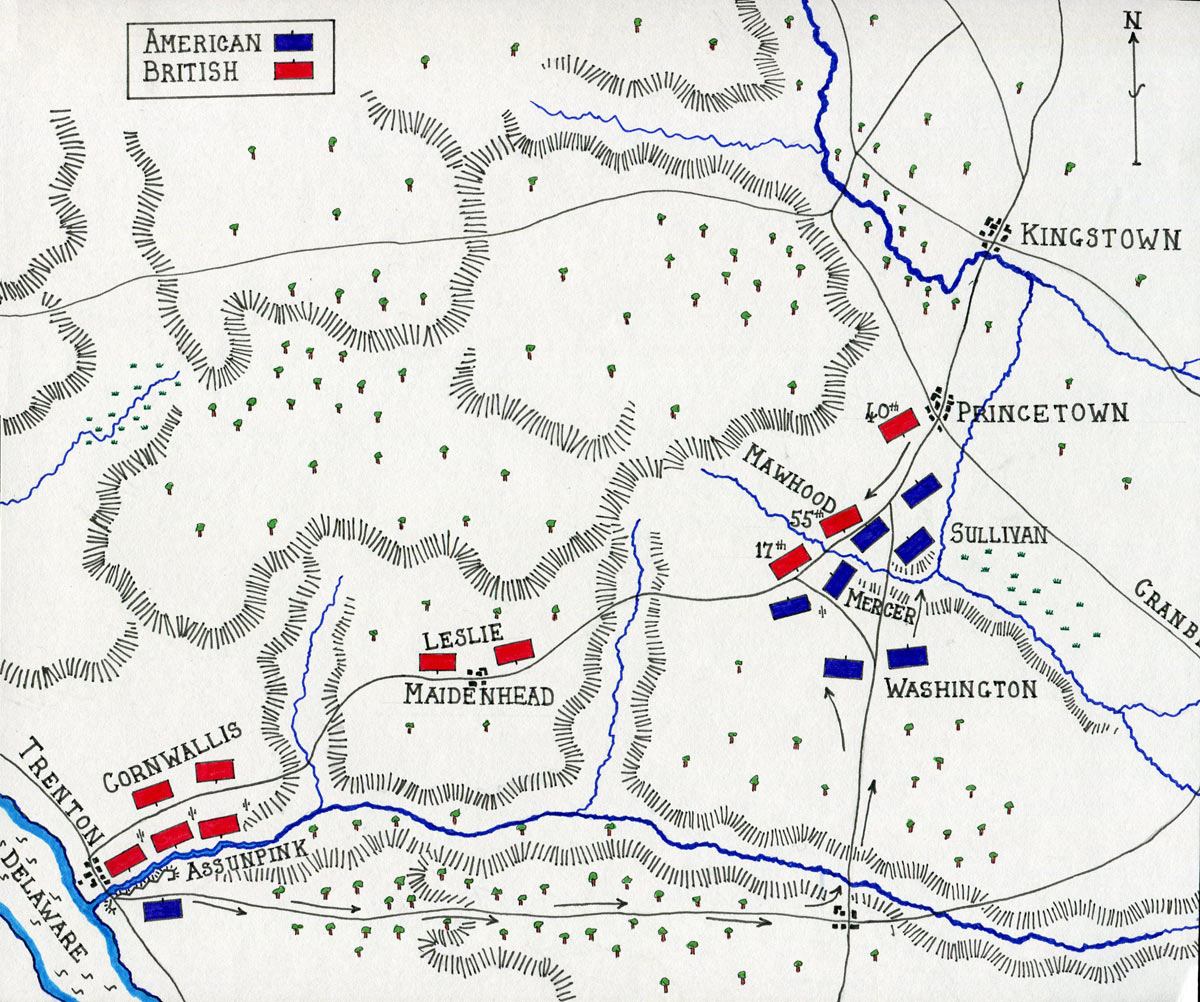

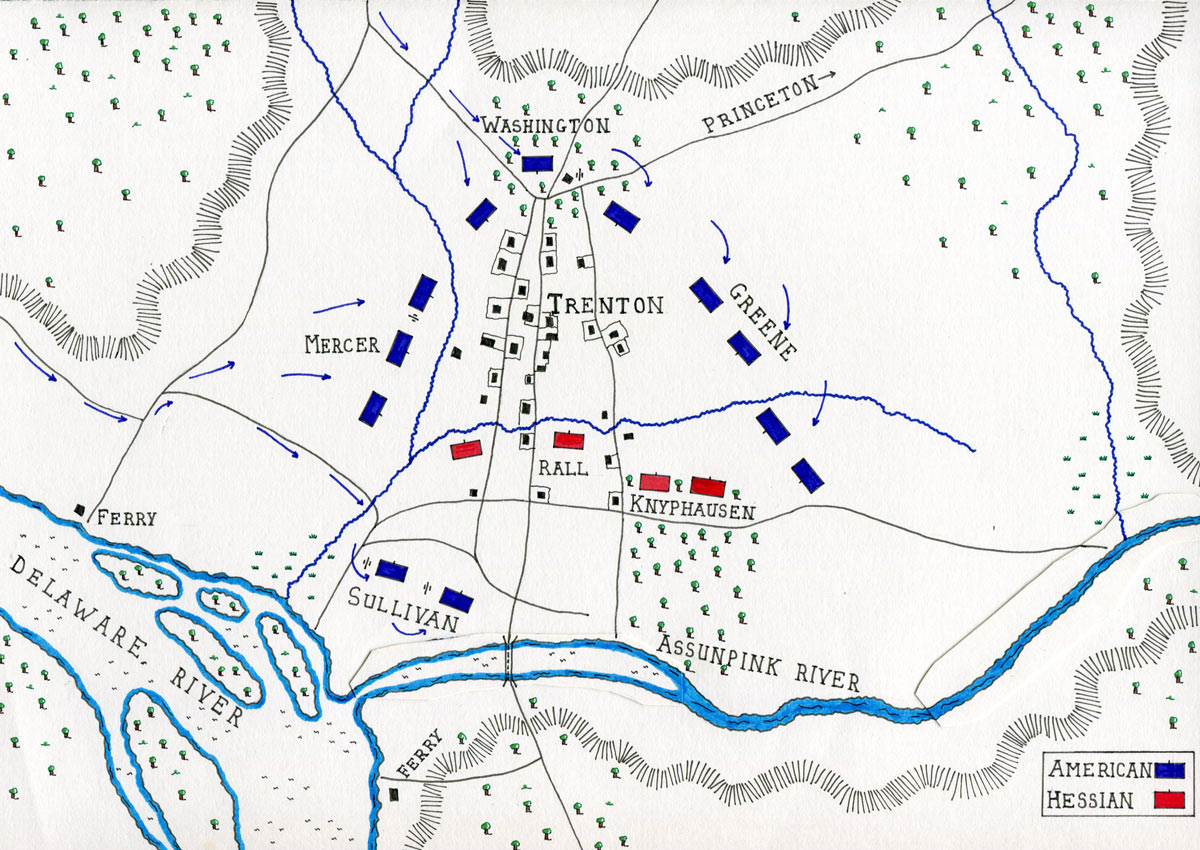

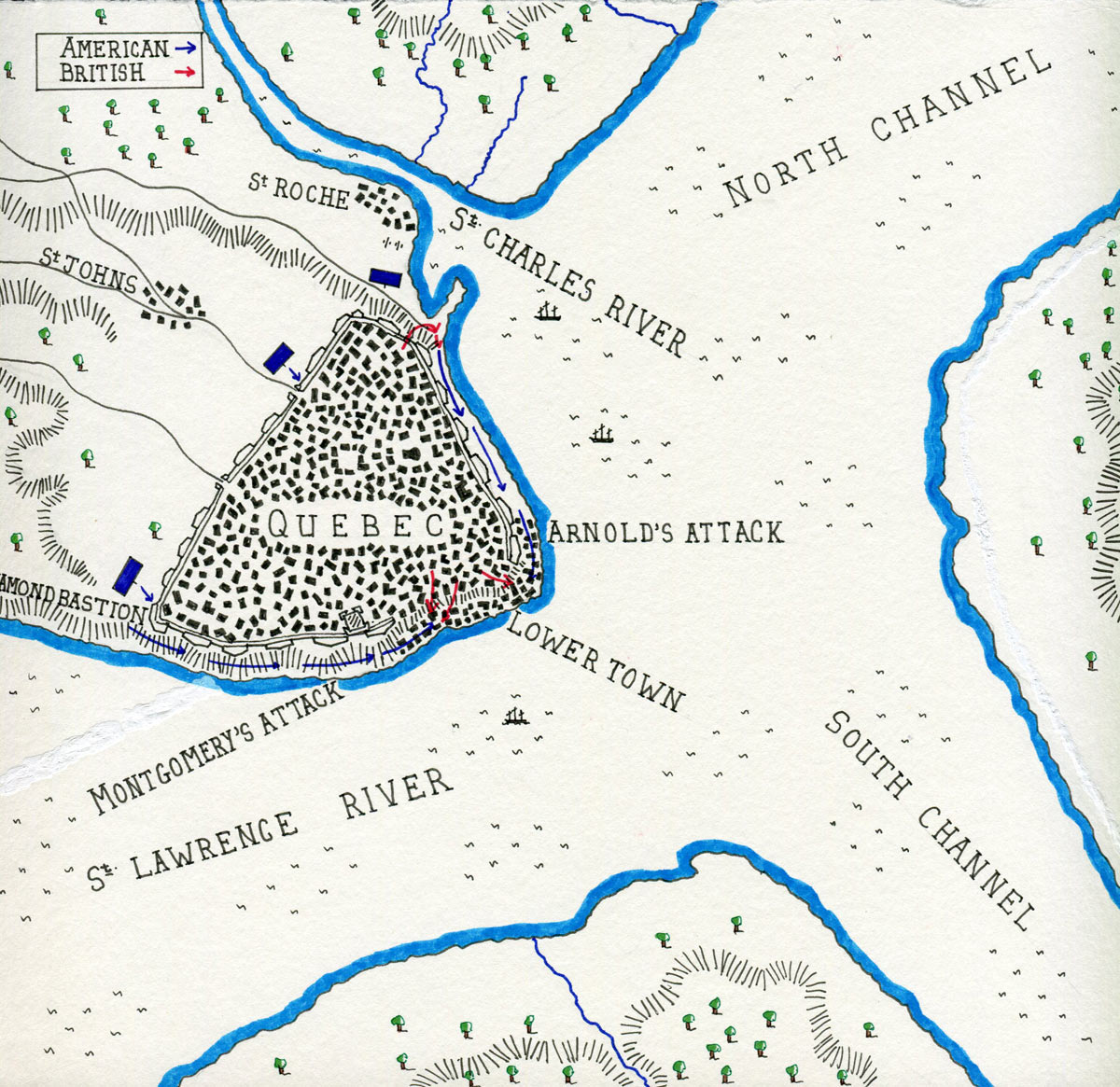

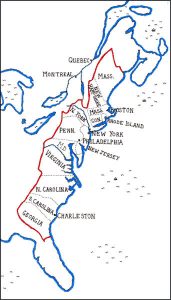

Map of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on 15th March 1781 in the American Revolutionary War: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse:

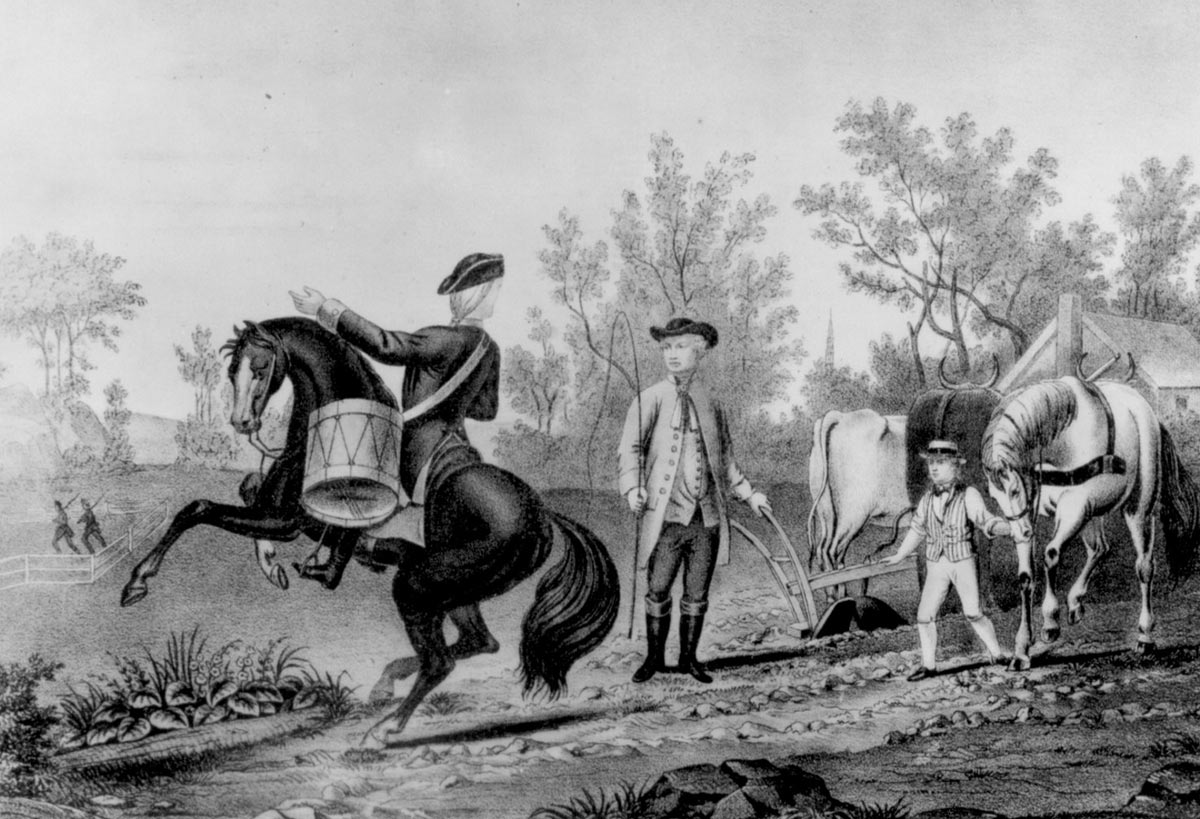

After two years of the toughest of campaigning in South and North Carolina, Major-General Lord Cornwallis pursued Major-General Nathaniel Greene’s American army, with the intention of defeating him, before launching the final and ill-fated British invasion of Virginia.

After a headlong march, in which he constantly kept ahead of the British force, Greene halted to give battle at Guilford in North Carolina. Greene formed his American army up at the Courthouse.

Light Company man 1st Foot Guards: Battle of Guilford Courthouse on 15th March 1781 in the American Revolutionary War

Cornwallis rushed to attack the Americans on the morning of 15th March 1781, his troops hungry and tired after the many days marching on short rations.

The British advanced up the road leading to Guilford in column of march, through thickly wooded country leading to an area cleared for grazing, a half-mile short of Guilford Courthouse. Beyond this cleared area, the woods continued until the road reached the Courthouse, where there was another large cleared area.

American Continental soldier: Battle of Guilford Courthouse on 15th March 1781 in the American Revolutionary War

The Americans were formed across the northern edge of the first clearing and into the woods on each side. This first line comprised the North Carolina militia, Washington’s Legion, Lee’s Legion, and Campbell’s riflemen. Lee’s and Washington’s cavalry took the flanks. While there were initially two guns in this first line, they were withdrawn as the battle began.

Three hundred and fifty yards further back, in the woods, was a second line of Virginia Militia and, at a similar distance to the rear, at the Courthouse, was the third American line of two more guns and Greene’s Continental Infantry.

On the advice of Daniel Morgan, Greene placed parties of riflemen behind the North Carolina militia with orders to shoot any militiaman who left his post before he had given the two discharges required of him.

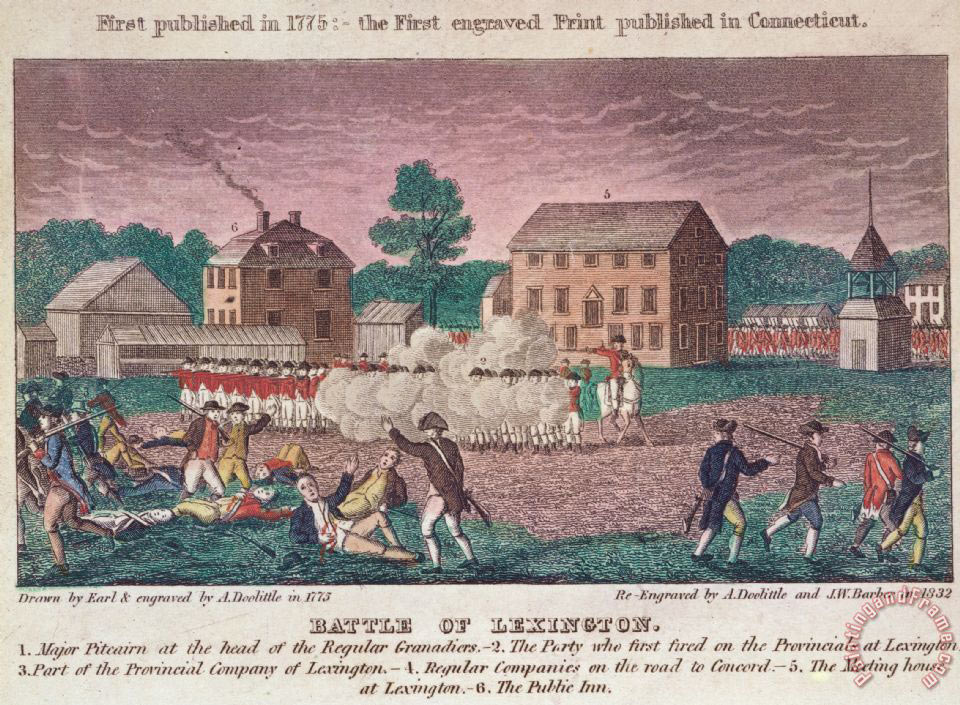

The Americans opened fire as the British appeared at the southern edge of the first clearing.

Cornwallis formed his first line with Bose’s Regiment and the 71st Highlanders on the right, commanded by Major-General Leslie, and the 23rd and 33rd Regiments, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James Webster of the 33rd, on the left.

1st Continental Regiment at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on 15th March 1781 in the American Revolutionary War

The British second line comprised the two battalions of Foot Guards, the Light Infantry and the Grenadiers, commanded by Brigadier O’Hara of the Coldstream Guards. Tarleton’s Light Dragoons formed the final reserve.

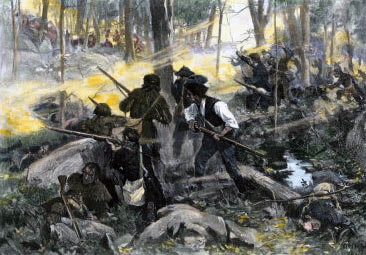

The British line advanced across the cleared area, under heavy musket fire which caused significant casualties. Once they were across the fencing with which the grazing was divided, the British Foot charged and the American militia, having delivered the two volleys ordered, hurried away into the woods.

The British were still under fire from the American troops in the woods on their flanks. The British first line split to deal with this threat and the grenadiers and one battalion of Foot Guards moved into the centre to fill the gap.

The British infantry now attacked the second line of Virginians, who had been reinforced by Washington’s and Lee’s men and some of the North Carolina militia.

Webster pushed hard at the right flank of the American second line and forced it back. His men then attacked the Continental troops in the third line. The American Continentals delivered a heavy fire, followed by a charge, which repelled Webster’s 33rd and O’Hara’s Jaegers and the Foot Guards.

Following the charge, the Continental regiments returned to their positions. The British left flank was reinforced by the 23rd and the 71st, returning from the woods on the British left, and the attack was renewed. The American infantry gave ground, but Washington’s dragoons charged the Foot Guards in the rear and an American counter attack led to a savage and confused melee.

At this crisis in the battle, Cornwallis ordered his three guns to fire grape shot into the struggling mass. American and Briton were struck down indiscriminately by this fire, but the American assault was repelled. To hurry the Americans on their way, Tarleton charged the American right flank.

Greene withdrew from the battlefield, leaving his guns to the British. There was no pursuit.

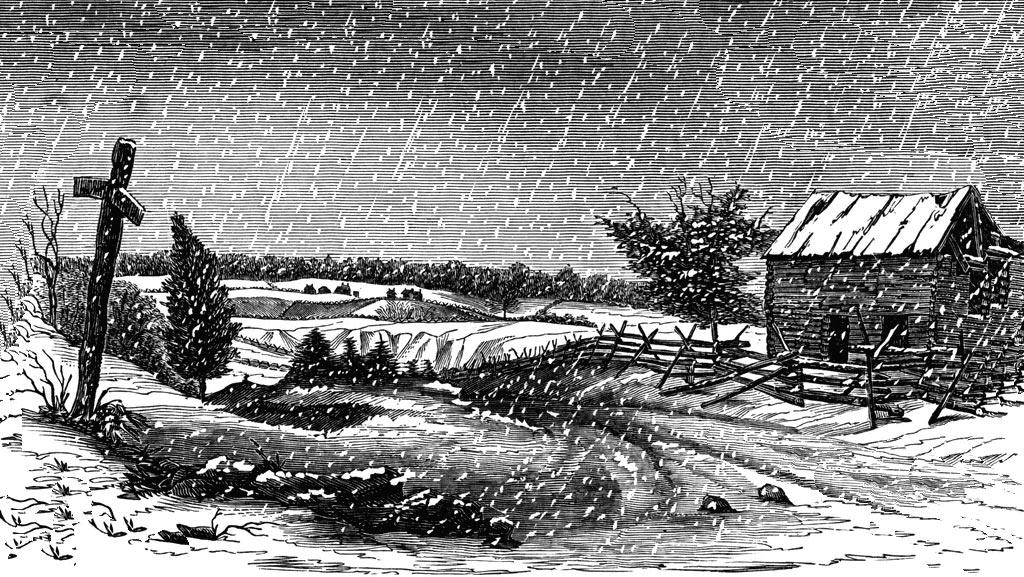

Cornwallis was left on the field, but his army was in a sad state. He had suffered heavy casualties, which could not be replaced. He had no supplies and it began to rain heavily. Webster, on whom Cornwallis relied, had been killed and O’Hara was wounded.

Battlefield of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on 15th March 1781 in the American Revolutionary War

Casualties at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse:

British casualties were 550 dead and wounded. The Foot Guards lost 11 officers out of 19 and 200 soldiers out of 450.

The American casualties were 250 killed, wounded and captured. In addition, the North Carolina militia did not return to Greene’s army after leaving the field, dispersing to their homes.

Follow-up to the Battle of Guilford Courthouse:

Following the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, Cornwallis began his move into Virginia, which led finally to Yorktown and the British Army’s surrender.

Traditions and anecdotes from the Battle of Guilford Courthouse:

- On the night before the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, General Nathaniel Greene and his troops camped around a tree that became known as the ‘Liberty Oak’.

- Daniel Morgan was yet another soldier of the American Revolutionary War who cut his teeth with General Edward Braddock in 1755. Morgan was a cousin of Daniel Boone and was one of Braddock’s teamsters in the doomed campaign against Fort Duquesne.

- A monument was erected near the battlefield to mark where ‘Bugler Boy’ Gillies, Colonel ‘Light Horse Harry’ Lee’s trumpeter was caught and killed by Tarleton’s Legion.

References:

History of the British Army by Sir John Fortescue

The War of the Revolution by Christopher Ward

The American Revolution by Brendan Morrissey

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Cowpens

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Yorktown

To the American Revolutionary War index